rog1a

THE RIGHTEOUSNESS OF GOD

by Ray Shelton

INTRODUCTION

While I was teaching the young adult class at the North Hollywood Evangelical Free Church in the late 1950’s, I taught the book of Romans. In preparing to teach Paul’s letter to the Romans, the Lord showed me the meaning of the righteousness of God which is the theme of that letter (Rom. 1:17). I had been taught in the theology and Bible courses that I had taken at BJU, Wheaton and Fuller, that the righteousness of God was the justice of God, that is, that attribute of God whereby God deals with man according to their works, rendering punishment to those who transgress His law and rewards and blessings to those who keep His law. This concept of righteousness implied that salvation is by meritorious works which is contrary to Scripture (Rom. 4:3-6; Eph. 2:8-9; Titus 3:5-8). In fact, the Reformation doctrine of justification by faith actually teaches that salvation or eternal life was earned for us by Christ’s active obedience, by the good works that Christ did during His life on earth, and that these merits of Christ are imputed to the account of those that believe. The Reformed doctrine of Justification is vicarious salvation by works. I could not find this doctrine in the Scriptures and in particular not in Romans; the Scriptures never speaks of the merits or the righteousness of Christ nor of them being imputed to the believers account. In fact, it says that “faith is reckoned as righteousness” (Rom. 4:5, 9, 22-25) and that faith excludes works. In my reading as I investigate this difficulty, I found that Luther had a problem with the concept of the righteousness of God as justice. But Luther attempted to solve the problem by denying the active meaning of righteousness (the attribute of God by which He punishes sin and rewards man’s good works) and by equating the righteousness of God with righteousness in a passive sense as that given by God, the righteousness from God. The Protestant scholastics after Luther accepted both senses and equated the passive righteousness with the merits of Christ that He earned for us by His active obedience. Because their explanation of the death of Christ was still grounded in the legalistic concept of justice, that is, that Christ died to pay the penalty for man’s sin which the justice of God requires to be paid before God can save man, they had to retain the active sense also. This concept of the righteousness of God is the doctrine that I was taught in the courses that I had taken. Then I came across the commentary on Romans by C. H. Dodd, The Epistle of Paul to the Romans and his book The Bible and the Greeks where he shows that the Biblical concept of righteousness of God is different from the Greek-Roman concept of justice. Instead of as an attribute, the righteousness of God is an act or activity of God where God puts right the wrong. In the Old Testament, it is the activity of God in which He delivers the oppress and vindicates the righteous, those who trust in the true God. The righteounsess of God is a synonym for the salvation of God which emphasizes deliverance from that which is wrong to that which is right. In the New Testament, the righteounsess of God is the activity of God whereby He sets the ungodly right with Himself.

The Protestant Reformation actually began, not when Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses upon the door of the Wittenburg church on 31st of October, 1517, but when Martin Luther rediscovered the meaning of the righteousness of God in Paul’s letter to the Romans. [1] This discovery was made at the end of a long and troubled search which began when at the age of 21, on July 17, 1505, Luther applied for admission to the monastery at Erfurt of the Augustinian Friars known as the Black Cloister because of their black habit. They were also known as the Augustinian Hermits. Having recently been made a Master of Arts at the University of Erfurt, Martin had gone home to Mansfeld on a vacation during the month of June, 1505. On July 2, when returning to Erfurt from Mansfeld, at a distance of about five miles from his university, close to the village of Stotternheim, he was overtaken by a thunderstorm. When one of the lightning bolts nearly struck him, he cried out in terror, “Help, St. Anne, and I’ll become a monk.” Later, in his DeVotis Monasticis (“Concerning Monastic Vows,” 1521) Luther explains his state of mind at that time.

“I was called to this vocation by the terrors of heaven, for neither willingly nor by my own desire did I become a monk; but, surrounded by the terror and agony of a sudden death, I vowed a forced and unvoidable vow.” [2]

Accordingly, he sold his books, bade farewell to his friends, and entered the monastery. Luther observed the canonical regulations as prescribed in the constitution of the Observatine section of the Augustinian Order of Mendicant Monks. He says:

“I was an earnest monk, lived strictly and chastely, would not have taken a penny without the knowledge of the prior, prayed diligently day and night.” [3] “I kept vigil night by night, fasted, prayed, chastised and mortified my body,was obedient, and lived chastely.” [4]

The purpose of it all was justification, being righteous with God.

“When I was a monk, I exhausted myself by fasting, watching, praying, and other fatiguing labors. I seriously believed that I could secure justification through my works…” [5] “It is true that I have been a pious monk, and followed my rules so strictly that I may say,if ever a monk could have gained heaven through monkery, I should certainly have got there. This all my fellow-monks who have known me will attest.” [6]

But all these observances did not bring peace to his troubled conscience. He says:”I was often frightened by the name of Jesus, and when I looked at him hanging on the cross, I fancied that he seemed to me like lightning. When I heard his name mentioned, I would rather have heard the name of the devil, for I thought that I had to perform good works until at last through them Jesus would become merciful to me. In the monastery I did not think about money, worldly possessions, nor women, but my heart shuddered when I wondered when God should become merciful to me.” [7]

Later in 1545 in the famous autobiographical fragment with which he prefaced the Latin edition of his complete works, Luther thus described his feelings:

“For however irreproachably I lived as a monk, I felt myself in the presence of God to be a sinner with a most unquiet conscience, nor could I believe that I pleased him with my satisfactions. I did not love, indeed I hated this just God, if not with open blasphemy, at least with huge murmurings, for I was indignant against him, saying, ‘as if it were really not enough for God that miserable sinners should be eternally lost through original sin, and oppressed with all kind of calamities through the law of the ten commandments, but God must add sorrow on sorrow, and even by the gospel bring his wrath to bear.’ Thus I raged with a fierce and most agitated conscience…” [8]

These inward, spiritual difficulties were intensified by a theological problem. This was the concept of the “righteousness of God” (justitia Dei). His religious background made him intensely aware of the justice of God, and he had learned the Greek concept of justice as found in book 5 of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Thus encouraged by the use of justitia in Gabriel Biel and other nominalists, he thought of God’s justice as being primarily the active, punishing severity of God against sinners as he explains in his exposition of Psalm 51:14 in 1532:

“This term ‘righteousness’ really caused me much trouble. They generally explained that righteousness is the truth by which God deservedly condemns or judges those who have merited evil. In opposition to righteousness they set mercy, by which believers are saved. This explanation is most dangerous, besides being vain, because it arouses a secret hate against God and His righteousness. Who can love Him if He wants to deal with sinners according to righteousness?” [9]

This conception blocked his understanding of St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans.

“All the while I was aglow with the desire to understand Paul in his letter to the Romans. But… the one expression in chapter one (v.17) concerning the ‘righteousness of God’ blocked the way for me. For I hated the expression ‘righteousness of God’ since I had been instructed by the usage custom of all teachers to understand it according to scholastic philosophy as the ‘formal or active righteousness’ in which God proves Himself righteous by punishing sinners and the unjust …” [10]

But God used this passage to change his understanding of the righteousness of God and to solve his inward, spiritual difficulties.

“Finally, after days and nights of wrestling with the difficulty, God had mercy on me, and then I was able to note the connection of the words ‘righteousness of God is revealed in the Gospel’ and ‘just shall live by faith.’ Then I began to understand the ‘righteousness of God’ is that through which the righteous lives by the gift (dono) of God, that is, through faith, and that the meaning is this: The Gospel reveals the righteousness of God in a passive sense, that righteousness through which ‘the just shall live by faith.’ Then I felt as if I had been completely reborn and had entered Paradise through widely opened doors. Instantly all Scripture looked different to me.

I passed through the Holy Scriptures, so far as I was able to recall them from memory, and gathered a similar sense from other expressions. Thus the ‘work of God’ is that which God works in us; the ‘strength of God’ is that through which He makes us strong; the ‘wisdom of God’ is that through which He makes us wise; and the ‘power of God,’ and ‘blessing of God,” and ‘honor of God,’ are expressions used in the same way.”

“As intensely as I had formerly hated the expression ‘righteousness of God’I now loved and praised it as the sweetest of concepts; and so this passage of Paul was actually the portal of Paradise to me.” [11]

This discovery not only brought peace to Luther’s troubled conscience but it was the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. Luther’s protest against the errors of the Roman Catholic church stems from this discovery. But his discovery was lost by those who came after him, the Protestant scholastics. Luther’s use of the scholastic distinction of active and passive righteousness tended to obscure the Biblical concept of the righteousness of God. Luther obviously rejected the active sense; but the later Lutheran protestant scholastics interpreted Luther as accepting both senses. Because their explanation of the death of Christ was still grounded in the legalistic concept of justice, that is, that Christ died to pay the penalty for man’s sin which the justice of God requires to be paid before God can save man, they had to retain the active sense also. Thus Luther’s discovery of the Biblical understanding of the righteousness of God was obscured and eventually lost.

By identifying the righteousness of God with the passive sense, Luther also gave the impression that the righteousness of God is the righteousness from God, that is, the righteousness that man receives from God through faith. But the righteousness from God is not the righteousness of God. These are different though related ideas and must be carefully distinguished. Paul writes in his letter to the Philippians,

“8b For his sake I have suffered the loss of all things, in order that I may gain Christ 9 and be found in him, not having a righteousness of my own, based on law, but that which is through faith, the righteousness from [ek] God that depends upon [epi] faith,…” (Phil. 3:8b-9).

Thus the righteousness from God is the righteousness of faith (Rom. 4:13) which is that right personal relationship to God that results from faith in the true God (Rom. 4:3). Paul writes in his letter to the Romans,

“3 For what does the scripture say? ‘Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness.’ 4 Now to one who works, his wages are not reckoned as a gift but as his due. 5And to the one who does not work but trusts him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is reckoned as righteousness ….

13 The promise to Abraham and his descendants, that they should inherit the world, did not come through the law but through the righteousness of faith.” (Rom. 4:3-5, 13)

Faith in God is reckoned as righteousness (Rom. 4:5). That is, to trust in God is to be righteous. This is the righteousness of faith (Rom. 4:13) and the righteousness from God (Phil. 3:9). The righteousness of God, on the other hand, is God acting to set man right with God Himself and, as we shall see below, it is synonymous with salvation.

The Biblical concept of the righteousness of God is the act or activity of God whereby He puts or sets right that which is wrong. [12] In the Scriptures, the righteousness of God is not an attribute of God whereby He must render to each what he has merited nor is it a quantity of merit which God gives, but is the act or activity of God whereby He puts or sets right that which is wrong. Very often in the Old Testament it is the action of God for the vindication and deliverance of His people; it is the activity in which God saves His people by rescuing them from their oppressors.

“In thee, O Lord, do I seek refuge; let me never be put to shame; in thy righteousness deliver me!” (Psa. 31:1)

“In thy righteousness deliver me and rescue me; incline thy ear to me, and save me!” (Psa. 71:2)

“11 For thy name’s sake, O Lord, preserve my life! In thy righteousness bring me out of trouble! 12 And in thy steadfast love cut off my enemies. and destroy all my adversaries,for I am thy servant.” (Psa. 143:11-12)

Thus the righteousness of God is often a synonym for the salvation or the deliverance of God. In the Old Testament, this is clearly shown by the literary device of parallelism which is a characteristic of Hebrew poetry. [13] Parallelism is that Hebrew literary device in which the thought and idea in one clause is repeated and amplified in a second and following clause. This parallelism of Hebrew poetry clearly shows that Hebrew poets and prophets made the righteousness of God synonymous with divine salvation:

“The Lord hath made known His salvation: His righteousness hath he openly showed in the sight of the heathen.” (Psa. 98:2 KJV)

“I bring near my righteousness, it shall not be far off, and my salvation shall not tarry; and I will place salvation in Zionfor Israel my glory.” (Isa. 46:13 KJV)

“My righteousness is near, my salvation is gone forth, and mine arms shall judge the people; the isles shall wait upon me, and on mine arm shall they trust.” (Isa. 51:5 KJV)

“Thus saith the Lord, keep ye judgment and do justice [righteousness]: for my salvation is near to come, and my righteousness to be revealed.” (Isa. 56:1 KJV; See also Psa. 71:1-2, 15; 119:123; Isa. 45:8; 61:10; 62:1)

From these verses, it is clear that righteousness of God is a synonym for the salvation or deliverance of God. Very often in the Old Testament the Hebrew nouns, tsedeq and tsedaqah, translated “righteousness,” is derived from the Hebrew verb, tsadaq. [14] Although the Hebrew verb is usually translated “to be righteous” or “to be justified,” the verb has the primary meaning “to be in the right” rather than “to be righteous.” (Gen. 38:26; Job 11:2; 34:5) [15] The causative form of the verb hitsdiq generally translated “to justify” means not “to make righteous” nor “to declare righteous” but rather “to put in the right” or “to set right.” (Ezekiel 16:51-55). Thus it very often has the meaning “to vindicate” or “to give redress to” a person who has suffered wrong. Thus the Hebrew noun tsedeq usually translated “righteousness” means an act of vindication or of giving redress. When applied to God, the righteousness of God is God acting to put right the wrong, hence to vindicate and deliver the oppressed. Thus the Biblical concept of the righteousness of God is the act or activity of God whereby He puts or sets right that which is wrong.

The righteous acts of the Lord, or more literally, the righteousnesses of the Lord, referred to in Judges 5:11; I Sam. 12:7-11; Micah 6:3-5; Psa. 103:6-8; Dan. 9:15-16, means the acts of vindication or deliverance which the Lord has done for His people, giving them victory over their enemies. It is in this sense that God is called “a righteous God and a Savior” (Isa. 45:21 RSV, NAS, NIV) and “the Lord our righteousness” (Jer. 23:5-6; 33:15-16).

A judge or ruler is “righteous” in the Hebrew meaning of the word not because he observes and upholds an abstract standard of Justice, but rather because he comes to the assistance of the injured person and vindicates him. For example, in Psalm 82:2-4 (NAS), God says to the rulers:

2 How long will you judge unjustly, And show partiality to the wicked? 3 Vindicate the weak and fatherless; Do justice [judgment] to the afflicted and destitute. 4 Rescue the weak and needy; Deliver them out of the hand of the wicked.” (Psalm 82:2-4 [NAS]. See also Psa. 72:4; 76:9; 103:6; 146:7; Isa. 1:17.)

For the judge to act this way is to show righteousness. (See Psa. 72:1-4.) A judge in the Old Testament is not one whose business it is to interpret the existing law or to give an impartial verdict in accordance with the established law of the land, but rather he is a deliverer and thus a leader and savior as in the book of Judges (Judges 1:16-17; 3:9-10). His duty and delight is to set things right, to right the wrong; his “judgments” are not words but acts, not legal verdicts but the very active use of God’s right arm. The two functions of a judge are given in Psalm 75:7 (NAS):

“But God is the judge: he puts down one and exalts another.” (Psalm 75:7 [NAS]).

Since this is a statement concerning God as a judge, it could be taken as a general definition of a Biblical judge. In Psa. 72:1-4, these two functions of Biblical judge are given to the king of Israel.

“1 Give the king thy judgments, O God, and thy righteousness unto the king’s son. 2 May he judge thy people with righteousness, and thy poor with judgment. 3 The mountains shall bring peace to the people, and the little hills, by righteousness. 4 He shall judge the poor of the people, he shall save the children of the needy, and break in pieces the oppressor.” (Psa. 72:1-4 KJV)

These same two functions are ascribed to the future ruler of Israel, the Messiah, according to Isaiah 11:3-5 (RSV).

“3 And His delight shall be in the fear of the Lord. He shall not judge by what his eyes see, or decide by what His ears hear; 4 but with righteousness he shall judge the poor, and decide with equity for the meek of the earth; and He shall smite the earth with a rod of His mouth; and with the breath of His lips He shall slay the wicked. 5 Righteousness shall be the girdle of His waist, and faithfulness the girdle of His loins.” (Isa. 11:3-5 RSV)

His righteousness is shown in His judging the poor, that is, in the vindication of those who are the victims of evil, the poor and meek of the earth, and in the smiting of the wicked who oppress them.

There is a difference between the righteousness of God in the Old Testament and that in the New Testament. In the Old Testament, the righteousness of God is the vindication of the righteous who are suffering wrong (Ex. 23:7). God vindicates the righteous who are wrongfully oppressed. In the Old Testament the righteousness of God requires a real righteousness of the people on whose part it is done. In Isa. 51:7, the promise of deliverance is addressed to those “who know righteousness, the people in whose hearts is my law.” Similarly, in order to share in the promised vindication, the wicked must forsake his ways and the unrighteous man his thoughts, and return unto the Lord (Isa. 55:7). In the New Testament, the righteousness of God is not only a vindication of a righteous people who are being wrongfully oppressed (this view is in Jesus’ teaching in Matt. 5:6; 6:33; Luke 18:7), but it is also a deliverance of the people from their own sins; it is also the salvation of the ungodly who are delivered from their ungodliness (trust in a false god) and unrighteousness. The righteousness of God saves the unrighteous by setting them right with God Himself through faith (Rom. 1:17a).

The righteousness of God is not opposed to the love of God nor does it condition the love of God. On the contrary, it is a part of and the proper expression of God’s love. It is the activity of God’s love to set right the wrong. In the Old Testament, this is shown by the parallelism between love and righteousness.

“But the steadfast love of the Lord is from everlasting to everlasting upon those who fear him, and his righteousness to children’s children.” (Psa. 103:17 RSV; see also Psa. 33:5; 36:5-6; 40:10; 89:14.)

God expresses His love as righteousness in the activity by which He saves His people from their sins. In His wrath, God opposes the sin that would destroy man whom He loves. In His grace, He removes the sin. The grace of God is the love of God in action to bring salvation.

“4 But God, who is rich in mercy, out of the great love with which He loved us, 5 even when we were dead in our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ (by grace you have been saved).” (Eph. 2:4-5)”For the grace of God that brings salvation has appeared to all men.” (Titus 2:11 NIV).

Thus the righteousness of God may be considered as the proper expression of the grace of God. For in His righteousness God acts to deliver His people from their sins, setting them right with Himself.

The righteousness of God is God acting in love for the salvation or deliverance of man. This righteousness of God has been manifested, that is, publicly displayed, in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

“21 But now apart from the Law the righteousness of God has been manifested, being witnessed by the Law and the Prophets; 22 even the righteousness of God through faith in Jesus Christ for all those who believe; for there is no distinction;” (Rom. 3:21-22 NAS).

The righteousness of God, as we have just seen, is God acting in love to set man right with God Himself and is synonymous with salvation (Ps. 98:2; 71:1-2, 15; 119:123; Isa. 45:8; 46:13; 51:5; 56:1; 61:10; 62:1). Now this righteousness of God has been manifested (phaneroo), that is, publicly displayed, in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. God was active in the death and resurrection of Christ for man’s salvation. And because He is this act of God for man’s salvation, Jesus Christ is the righteousness of God (I Cor. 1:30). And since the gospel or good news is about Jesus Christ, who He is and what He did (Rom. 1:3-4; I Cor. 15:3-4), it is about this manifestation of the righteousness of God. The gospel tells us about God’s act of salvation in the person and work of Jesus Christ; the gospel is the gospel of our salvation (Eph. 1:13).

But the gospel is not only about the righteousness of God manifested in the past on our behalf, but in the preaching of the gospel the righteousness of God is being continually revealed (apokalupto) in the present.

“For in it [the gospel] the righteousness of God is being revealed from faith unto faith” (Rom. 1:17a ERS).

The revelation that is spoken of in this verse is not just a disclosure of truth to be understood by the mind, but it is a working that makes effective and actual that which is revealed. Hence, the revelation of the righteousness of God is that working of God that makes effective and actual that which is revealed, that is, the righteousness of God. [16] In other words, the revelation of the righteousness of God is the actualization of God’s salvation. And the righteousness of God is revealed when the salvation of God is made actual and real, that is, when salvation or deliverance takes place. Thus in the preaching of the gospel there is taking place continually an actualization of the righteousness of God. In other words, salvation or deliverance is taking place as the gospel is preached. This is the reason that the gospel is the power of God unto salvation (Rom. 1:16. Compare Rom. 1:16-17 with Isa. 56:1 which is, no doubt, the source of Paul’s concepts and words in these verses.)

The gospel not only tells us about this manifestation of the righteousness of God, but also in the gospel the righteousness of God is being continually revealed or made effective and actual (Rom. 1:17a). When the gospel is preached, God is acting to set man right with Himself. The result of God’s activity of righteousness is the righteousness of faith, the righteousness from God, since it has been received from God by faith. God in His righteousness sets man right with Himself and through faith man is set right with God; faith rightly relates man to God. The righteousness of God is what God does and the righteousness of faith is what man does in response to God’s activity. The righteousness of faith is the righteousness from God because faith, which is man’s response to the word of God, comes from God (Rom. 10:6-8, 17); that is, in a sense, faith is “caused” by the word of God, even though it is man who does the believing and trusting.

This Biblical concept of the righteousness of God must be carefully distinguished from the Greek-Roman concept of justice. The righteousness of God in the Scriptures is not an attribute of God whereby He must render to each what he has merited nor a quantity of merit which God gives, but it is God acting to set right man with God Himself. Luther’s apparent identification of the righteousness of God with the righteousness from God lead eventually to the equating of the righteousness from God with Christ’s righteousness, that is, the merits of Christ, which Christ earned by His active obedience before He died on the cross and is imputed to the believer’s account when he believes. Scripture is often misinterpreted in terms of this identification.

For example, Paul’s statement that “in him we might become the righteousness of God” (II Cor. 5:21b) is interpreted to mean that the righteousness of God is the righteousness from God. Therefore, the believer is righteous by the “righteousness of God in Christ” which is interpreted as the merits of Christ that was earned by Christ’s active obedience before He died on the cross. Thus righteousness is misunderstood as merits and the righteousness of God as the justice of God. But the righteousness from God is not the righteousness of God. These are different though related ideas and must be carefully distinguished. Now since the righteousness of God, as we saw above, is God setting right the wrong, then the righteousness of God here is the deliverance or saving of us from our sins in Him, in Christ’s death and resurrection. But the righteousness from God is the righteousness of faith. Paul writes in his letter to the Philippians,

“8b For his sake I have suffered the loss of all things, in order that I may gain Christ 9and be found in him, not having a righteousness of my own, based on law, but that which is through faith, the righteousness from [ek] God that depends upon [epi] faith,…” (Phil. 3:8b-9).

Thus the righteousness from God is the righteousness of faith (Rom. 4:13) which is that right personal relationship to God that results from faith in the true God (Rom. 4:3). Paul writes in his letter to the Romans:

“3 For what does the scripture say? ‘Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness.’ 4Now to one who works, his wages are not reckoned as a gift but as his due. 5And to the one who does not work but trusts him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is reckoned as righteousness ….

13The promise to Abraham and his descendants, that they should inherit the world, did not come through the law but through the righteousness of faith.” (Rom. 4:3-5, 13)

Faith in God is reckoned as righteousness (Rom. 4:5). That is, to trust in God is to be righteous. This is the righteousness of faith (Rom. 4:13) and the righteousness from God (Phil. 3:9). That is, the righteousness of faith is not merit placed to the account of the believer, but it is the right relationship of the believer to God by faith. The righteousness of faith is the act or choice of a man to trust God and the righteousness of God is the act or activity of God to set a man right with God Himself by faith. The righteousness of God is what God does and the righteousness of faith is what man does in response to God’s activity. Thus the righteousness of faith is not the righteousness of God.

Now the righteousness of faith is the righteousness from God. Since this act of faith by a man is possible only when God acts to set a man right with God Himself by the righteousness of God, then the righteousness of faith is the righteousness from God. But as we just saw, this righteousness of faith is not the righteousness of God. Thus the righteousness from God is not the righteousness of God. Luther’s apparent identification of the righteousness from God with the righteousness of God was wrong and unscriptural.

This misinterpretation of this Scripture (II Cor. 5:21b) is based on a legalistic misunderstanding of the righteousness of God as the justice of God. But as we saw above, the Biblical concept of the righteousness of God is not this justice. This legalistic misunderstanding reduces and equates the righteousness of God to justice, that is, the giving to each that which is his due to them with a strict and impartial regard to merit (as in Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics). It is this concept of righteousness that gave Luther so much trouble.

Now this idea that the righteousness of God is the justice of God, that is, that attribute of God which requires that God punish all sin and reward all meritorious works, also leads to the misinterpretation of the first part of II Cor. 5:21 (“For our sakes he made him to be sin who knew no sin,”), that the sinless Christ was identified with the sin of the sinner, including the guilt of that sin and its consequence of death, of separation from God, and He paid the consequences of that sin by His death on the cross. This intrepretation is based on the penal substitution theory of the atonement. But this substitution interpretation must here be rejected because it is contrary to the explicit statement in the verse which says that he was made sin “for us”, that is, “on our behalf” (huper hemos, NAS; see verses II Cor. 5:14-15, and 20), not “instead of” as a substitute.

But since the phrase “made sin” may mean “scarifice for sin” (or “sin-offering”), Paul may be only intending to say no more than that Christ was made a sin-offering. But Christ was made to be a sin-sacrifice for us to save us from sin, to take away our sin (John 1:29). Thus Christ was made a sin sacrifice to take away our sin “in order that we might become the righteousness of God in Him” (II Cor. 5:21b ERS).

That is, that we might be set right with God in the risen Christ.

And as we have already seen, the righteousness of God is the activity of God to set us right with God; that is, to save us from sin (trust in false god) to righteousness (trust in the true God). As Christ was made a sin-scarifice for us, He participated in our spiritual death to save us from sin (trust in a false god), so that we could participate in the risen Christ, being saved from death to life and hence being saved from sin to righteousness (trust in the true God). Thus “we might become the righteousness of God in Him” (II Cor. 5:21b ERS). That is, that we might be saved (“the righteousness of God”) in the risen Christ.

Faith is the actualization of the righteousness of God, the salvation of God. This is expressed by Paul in Romans 1:17a in a twofold way: “from faith unto faith”. These prepositional phrases modify the verb “being revealed”, not the words “the righteousness of God.” The revelation is “from faith unto faith.”

1. Faith is the source of the revelation of the righteousness of God: “from faith”. The revelation of the righteousness of God arises out of or comes out of faith. That is, the actualization of the deliverance of God is the faith which the righteousness of God produces. The righteousness of God is revealed only when the one to whom the revelation comes has faith. Without faith there is no revelation, and only when there is faith is there a revelation, an actualization, of the righteousness of God. In this sense, faith is the source of the revelation of the righteousness of God. [16]

2. Faith is goal of the revelation of the righteousness of God: “unto faith”. The revelation of the righteousness of God moves toward and is accomplished in faith. When a man has faith, the deliverance of God has reached its goal. Faith then is the goal of the revelation of the righteousness of God.

Faith is not the means nor the condition of salvation but is the actualization of salvation. Salvation is not a thing which is received by faith but is God’s activity of deliverance which produces faith and is accomplished in that faith. In salvation, God does not give us something but gives us Himself, and faith is not receiving of something but is the receiving of Him. In salvation God does not just reveal something about Himself but reveals Himself. Apart from this personal revelation, faith is impossible, but when this revelation take place, faith is possible. Since “faith comes from hearing and hearing by the word of Christ” (Rom. 10:17), faith is the product of God’s activity of the revelation of Himself. This revelation takes place in the preaching of the gospel. For the gospel is the power of God unto salvation (Rom. 1:16). The gospel is not only about salvation (Eph. 1:13), but it is the power of God unto salvation. When the gospel is preached, God exerts His power and men are saved. This act of God’s power through the preaching of the gospel takes the form of the personal revelation of God Himself and His love. For He is love (I John 4:8, 16). Those who believe in response to this revelation are through this decision of faith realizing the power of God unto salvation, and in this decision of faith they are saved. To believe is to be saved, and to be saved is to believe.

In this decision of faith, they who believe are saved from death to life. To have faith in God is to believe in Jesus Christ, His Son (John 14:1; 6:29; 8:42; 5:38). And to believe in Jesus Christ is to receive spiritual life. For Jesus is the life (John 5:26; 6:33-35, 38-40, 57-58). For to believe in Jesus is to receive Him and to have received Jesus is to have the Son of God and to have the Son is to have life.

“11 And this is the testimony, that God gave us eternal life, and this life is in His Son. 12 He who has the Son has life; he who has not the Son of God has not life.” (I John 5:11-12)

To have life is to have passed from death to life.

“Truly, truly, I say to you, he who hears my word and believes Him who sent me has eternal life; he does not come into judgment, but has passed from death to life.” (John 5:24)

The one who believes has passed from death to life because he has in the decision of faith also identified himself with the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Christ identified Himself with us in death; He entered into our spiritual death on the cross and died physically for us. His death was our death. In faith, we accept His death as our death. In faith, we identify ourselves with Him in His death.

His death is our death. But since God has raised Jesus from the dead, so we also are raised from the dead and are made alive with Christ. His resurrection was our resurrection. In faith, we identify ourselves with Him and His resurrection. To receive life in Christ is to be raised from the dead with Him. To pass from death to life is to have died and been raised with Jesus from the dead. We are now spiritually alive in Him. We have entered into fellowship with God and are now reconciled to God. As the gospel is preached, God exerts His power and men are made alive, raised from the dead. Jesus said,

“Truly, truly, I say to you, the hour is coming, and now is, when the dead will hear the voice of the Son of God, and those who hear will live.” (John 5:25)

When the good news of the death and resurrection of Jesus for us is proclaimed, God speaks to men, revealing Himself in Jesus Christ. Those who hear and believe in Jesus are made alive in Him, being raised from the dead. They are reconciled to God (II Cor. 5:20). They are saved from death to life. Reconciliation is salvation from death to life.

And in the decision of faith, men are not only saved from death to life but also from sin to righteousness. God not only acted in Jesus Christ to reconcile us to Himself, that is, to deliver us from death to life, but also to redeem us from sin.

“In Whom [Christ] we have our redemption through His blood, the deliverance from our offenses, according to the riches of His grace” (Eph. 1:7 ERS; see also Col. 1:14).

The redemption that is in Christ (Rom. 3:24) is deliverance from sin by the payment of a price, a ransom, which is the blood of Christ, that is, His sacrificial death. The price is not the payment of a penalty but is the means by which the redemption from sin is accomplished.

“18Knowing that ye were not redeemed with corruptible things, like silver or gold, from your vain manner of life handed down from your fathers; 19 but with the precious blood, as of a lamb without blemish and without spot, even the blood of Christ.” (I Pet. 1:18-19 ERS; see also Heb. 9:14-15).

Redemption is the deliverance from sin as a slave master by means of the death of Christ [His blood] as the price or ransom.

“In Him we have redemption through His blood, the deliverance from our offenses, according the riches of His grace…” (Eph. 1:7 ERS). “In whom we have redemption, the deliverance from sins. (Col. 1:14 ERS).

According to the English translations of Eph. 1:7 and Col. 1:14, redemption seems to be made equivalent to forgiveness of sins.

“In Him we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of our trespasses, according the riches of his grace…” (Eph. 1:7 RSV). “In whom we have redemption,the forgiveness of sins. (Col. 1:14 RSV).

But the basic meaning of the Greek word aphesis here translated “forgiveness” is “the sending off or away.” Hence to redeem from sins is to send them away, to deliver from sin. Jesus “was manifested in order to take away sins” (I John 3:5 ERS). He is “the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29).

Salvation is not just forgiveness. It is more than forgiveness of sins; it is also deliverance from death; it is the resurrection of the dead. Forgiveness of sins is not enough; man needs to be made alive to God because he is spiritually dead. And he is dead, not because of his own sins, but because of the sin of another, Adam ( Rom. 5:12). So the forgiveness of a man’s sins does not take away spiritual death because the spiritual death was not caused by that man’s sins. Thus forgiveness of sins does not remove spiritual death. But the removing of spiritual death does remove sins. Salvation as resurrection from the dead is also salvation from sin and thus it is also the forgiveness of sins. Thus to be made alive to God means that sins are forgiven.

This redemption from sin was accomplished by the death of Jesus Christ because His death is also the means by which we were delivered from death, the cause of sin. Since spiritual death leads to sin (Rom. 5:12d ERS), sin reigns in the sphere of death’s reign (Rom. 5:21). And since Christ’s death is the end of the reign of death for those who died with Christ, it is also the end of the reign of sin over them. They are no longer slaves of sin, serving false gods. Sin is a slave master (Rom. 6:16-18) and this slave master is the false god in which the sinner trusts. We were all slaves of sin once, serving our false gods when we were spiritually dead, alienated and separated from the true God, not knowing Him personally. But we were set free from this slavery to sin through the death of Christ. For when Christ died for us, He died to sin (Rom. 6:10a) as a slave master. Sin no longer has dominion or lordship over Him. For he who has died is freed from sin (Rom. 6:7). That is, when a slaves dies, he is no longer in slavery, death frees him from slavery. Since Christ “has died for all, then all have died” (II Cor. 5:14). His death is our death. Since we have died with Him and He has died to sin, then we have died to sin. We are freed from the slavery of sin and are no longer enslaved to it (Rom. 6:6-7). But now Christ is alive, having been raised from the dead, and we are made alive to God in Him. His resurrection is our resurrection. “But the life He lives He lives to God” (Rom. 6:10b). This is the life of righteousness, the righteousness of faith. And so we, who are now alive to God in Him, are to live to righteousness. For just as death produces sin, so life produces righteousness.

“And He Himself bore our sins in His body on the cross, that we might die to sin and live to righteousness; for by His wounds you were healed.” (I Pet. 2:24)

Christ bore our sins to take them away (to redeem us from sin) so that we might die to sin with Christ and be made alive to righteousness in His resurrection. Having been redeemed from the slavery of sin through the death of Christ, we who are now alive in Him have become slaves of righteousness (Rom. 6:17-18), that is, slaves of Christ who is our righteousness (I Cor. 1:30). Redemption is salvation from sin to righteousness.

Since in those days of the Old and New Testament, slaves were also sold at the market, to buy a slave at the slave market could also be called “redemption.” The context of the verbs translate “to redeem” is not the law court but the slave market and it has nothing to do with “paying the penalty.” The purchase price or ransom is not the penalty for breaking the law but it is the means by which the purchase is accomplished. A ransom is given instead or in place of those who are to be redeemed or delivered; it has nothing to do with a substitute paying the penalty of sin to satisfy the justice of God. The context of the words translated “to redeem” or “redemption” is not the law nor the courtroom but slavery and the slavemarket. The redemption of Israel from bondage in Egypt has nothing to do with a substitute paying the penalty of sin; and neither does the redemption in Christ Jesus by His death [His blood] have to do with a substitute paying the penalty of sin, but with delivering us from bondage and setting us free from the slavery of sin.

What is sin? The analysis of human freedom shows that every man must have a god. By the very constitution of his freedom, man must have an ultimate criterion of decision. That is, behind every decision as to which thing a man should do or think, there is a reason, a criterion of decision. And the ultimate reason for any decision, practical or theoretical, must be given in terms of some particular criterion, an ultimate reference or orientation point in or beyond the self or person making the decision. This ultimate criterion is that person’s god.

Thus every man must then choose something as his god. If he does not choose the true God as his ultimate criterion of decision, he will choose a false god. He will choose some part or aspect of reality as his god, deifying it.

“They exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshipped and served the creature rather than the Creator.”

(Rom. 1:25)

The choice of a false god and the consequent personal allegiance and devotion to it is what the Bible calls idolatry. An idol does not have to be an image of wood, stone, or metal. It may be money, wealth, power, pleasure, education, the family, mankind, the state, democracy, experience, reason, science, the moral law, etc. An idol is a false god, and a false god may be anything, which may be good in its proper place, that takes the place of the true God, anything a person chooses as his or her ultimate criterion of decision, exalting it as God. Thus an idol is any substitute or replacement for the true God in a person’s life.

Since a false god usurps the place of the true God in a person’s life, idolatry is the basic sin. This sin is directly against the true God; it is a direct insult to Him and an affront to His divine majesty. No more serious sin could be imagined than this one. Since it is the most serious sin, it is therefore the most basic. This is the main reason that idolatry is the first sin prohibited by the Ten Commandments.

“Thou shalt have no other gods besides me.” (Exodus 20:3)

Thus idolatry is the basic sin, not pride; pride is not even mentioned in the Ten Commandments. Idolatry is also the basic sin because this sin leads to other sins. It leads to other sins since a person’s god, being his ultimate criterion of decision, will determine the choices he or she will make. The choice of a wrong god will lead to other wrong choices. That is, the idol that a person sets up in his heart (Ezek. 14:35) will affect the character and quality of his whole life. Idolatry is therefore the basic sin.

As faith in false god is the basic sin, so faith in the true God is righteousness. And to have faith in God is to acknowledge Jesus as Lord. In general, faith is not just belief that certain statements are true but is the commitment of oneself and allegiance to something or someone as one’s own personal ultimate criterion of all decisions, intellectual and moral. Saving faith in Jesus Christ is the commitment of oneself to Jesus Christ as one’s own personal ultimate criterion (“My Lord and my God,” John 20:28). The living person, the resurrected Jesus Christ, not just what He taught, becomes in the decision of faith our ultimate criterion. This decision of faith is a turning from false gods (idols) to the living and true God (I Thess. 1:10). Faith in the true God is righteousness.

“Abraham believed God, and it [his faith] was reckoned to him as righteousness.” (Rom. 4:3)

To believe God is to be righteous.

“But to the one who does not work, but believes in Him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is reckoned as righteousness.” (Rom. 4:5) (See also Rom. 4:22-24).

To acknowledge Jesus as Lord is to believe God that He raised Jesus from the dead.

“9 That if you confess with your mouth Jesus as Lord, and believe in your heart that God raised Him from the dead,

you will be saved; 10 For with the heart man believes unto righteousness, and with the mouth he confesses unto salvation.” (Rom. 10:9-10; ERS).

To believe God that He raised from the dead Jesus, who in faith we confess as Lord, is to be righteous. Thus, this decision of faith is salvation from sin to righteousness.

But in this decision of faith, men are not only saved from death to life and from sin to righteousness but also from wrath to peace. Since the wrath of God – God’s “no” or opposition to sin – is caused by sin (trust in a false god) (Rom.1:18), the removal of this sin brings with it also the removal of the wrath of God – no sin, no wrath. Now faith in Christ is also faith in the death of Christ for us; his death is our death. Since Christ’s death was the means that God has provided for turning away His wrath, His death is a propitiation for our sins; faith in Christ’s death turns away God’s wrath.

“24 Being set right freely by his grace through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus: 25 whom God set forth as a propitiation through faith in his blood …. (Rom. 3:24-25; ERS).

Faith in Christ’s death (His blood) turns away God’s wrath, since God has appointed his sacrificial death as the means to turn away His wrath. The result is peace with God; God is no longer opposed to man’s sin, since the sin has been removed by Christ’s death and resurrection. By faith in His death and resurrection we are set right with God.

“Being therefore set right by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ.” (Rom. 5:1 ERS)

“Much more then, being set right by his blood, we shall be saved from wrath through him.” (Rom. 5:9 ERS)

Thus, this decision of faith is also salvation from wrath to peace with God.

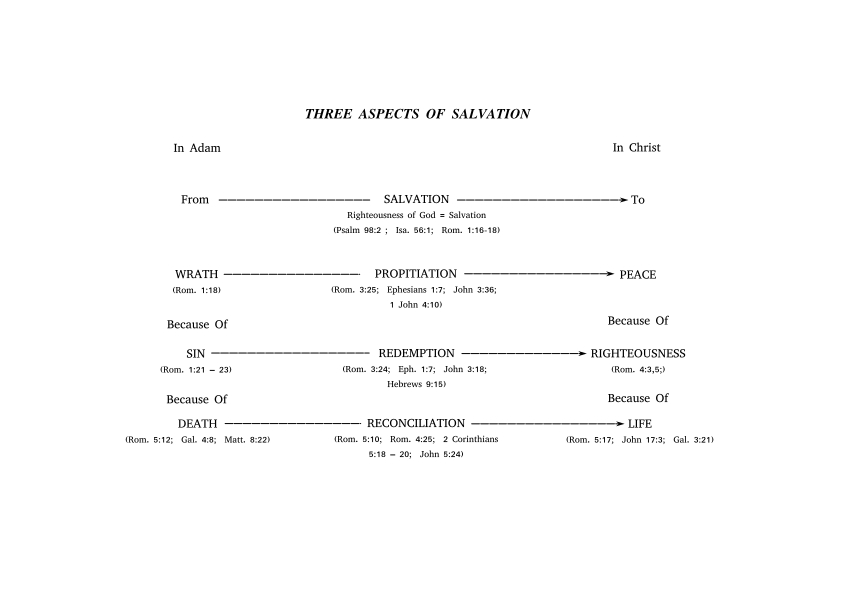

God in His righteousness has acted in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ for the salvation of man from the wrath, sin and death to peace, righteousness and life. Since wrath is caused by sin (Rom. 1:18) and sin by death ( Rom. 5:12d ERS), salvation is basically from death to life and then from sin to righteousness and then from wrath to peace with God. Thus there are three aspects of salvation:

(1) propitiation is salvation from wrath to peace;

(2) redemption, is salvation from sin to righteousness; and

(3) Reconciliation is salvation from death to life.

These three aspects of salvation are accomplished in and through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Christ’s death is a propitiation because it is a redemption; and it is a propitiation and a redemption because it is a reconciliation to God. Thus God has acted in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ for the salvation of man from death, sin and wrath to life, righteousness and peace with God.

These Three Aspects of Salvation are accomplished through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Propitiation is the sacrifical aspect of His work, redemption is the liberation aspect of His work, and reconciliation is the representative aspect of His work of salvation.

This threefold act of God for the salvation of man is the righteousness of God. The righteousness of God (salvation) has been manifested (publicily displayed) in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ (Rom. 3:21-26). The gospel tells us about this act of God, about this manifestation of the righteousness of God. And in the preaching of the gospel the righteousness of God is being continually revealed or actualized (Rom. 1:17). That is, God is exerting His power for the salvation of man in the preaching of the gospel (Rom. 1:16); in this activity man is being delivered from something bad, from wrath, sin and death, to something good, to peace, righteousness and life.

To Continue, Click here.

ENDNOTES

KJV King James Version, 1611 RV English Revised Version, 1881-1885 ARV American Revised Version, 1901 GNB Good News Bible, 1976 NAS New American Standard, 1971 NEB New English Bible, 1961-1970 NIV New International Version, 1978 ERS My own translation from the Greek or Hebrew

[2] Quoted in Albert Hyma, New Light on Martin Luther (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1958), p. 16.

[3] Luther, Commentary on the Gospel of John Weimer ed., XXXIII, 561. Dated 21, 1531, quoted in Hyma, p. 28.

[4] Luther, op. cit., dated October 28, 1531, p. 574, quoted in Hyma, p. 28.

[5] Luther, Exposition on Psa. XLV, p. 29.

[6] Luther, Answer to Duke George’s Latest Book quoted in Hyma, pp. 28-29.

[7] Luther, Sermon on Matthew XVIII-XXIV, pp. 29-30.

[8] Library of Christian Classics, Vol. XV, Luther: Lectures on Romans (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1961), pp. xxxvi-xxxvii.

[9] What Luther Says, Vol. III, Complied by Ewald M. Plass (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1959), p. 1225.

[10] What Luther Says, Vol. III, p. 1225-1225.

[12] Alan Richardson, An Introduction to the Theology of the New Testament, (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1958), pp. 79-83, 232-233.

[13] Edward J. Young, An Introduction to the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1950), pp. 281-282.

See also Gleason L. Archer, Jr., A Survey of Old Testament Introduction, (Chicago: Moody Press, 1964), pp. 418-420.

[14] C. H. Dodd, The Epistle of Paul to the Romans (London and Glasgow: Fontana Books, 1959), p. 38.

[15] C. H. Dodd, The Bible and the Greeks (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1964), p. 46.

[16] Burton on Galations in the ICC in contrasting phaneroo and apokalupto points out that “for some reason apokalupto has evidently come to be used especially of a subjective revelation, which either takes place wholly within the mind of the individual receiving it, or is subjective in the sense that it is accompanied by actual perception and results in knowledge on his part: Rom. 8:18; I Cor. 2:10; 14:30; Eph. 3:5.”

Ernest deWitt Burton, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Epistle to the Galations, in The International Critical Commentary (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1896), p. 433.

He goes on to say that “phaneroo throws emphasis on the fact that that which is manifested is objectively clear, open to perception. It is thus suitably used of an open and public announcement, disclosure or exhibition: I Cor. 4:5; II Cor. 2:14; 4:10-11; Eph. 5:13.” Ibid.

The use of the word apokalupto by Paul in Rom. 1:17 thus seems to place an emphasis on something happening to the individual receiving the revelation. The word “subjective” is probably not the right word to use to describe this event because it suggests that the source of revelation is from within the individual, the subject. Clearly the revelation that Paul is speaking of is from without the individual, and from God. But it does make a difference, a change; a response does take place in the person receiving the revelation. It does bring about that which is revealed, salvation.