poper1

THE PROBLEM OF PERFECTION

by Ray Shelton

I. THE STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

Jesus commanded in the Sermon on the Mount,

“Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect” (Matt.5:48).

This command of Jesus raises the problem of perfection: what is it to be perfect? Or more generally, what is perfection? In order to obey this command of Jesus, we must determine what is the meaning of word “perfect”, of what he is commanding.

In order to solve this problem, let us first analyze the meaning of the word “perfect” and then look at the various meanings historically that have been given to the concept of perfection starting with the Greek philosophers.

The Greek word in Matt. 5:48 that is translated “perfect” is teleios. This Greek adjective is derived from the noun telos which means “end” or “goal”. That is, it is the termination or limit of an act or state; in the New Testament it is used also of an end of period of time or a series of events (Luke 1:33; I Cor. 10:11; II Cor. 3:13; I Pet. 4:7). It is also used as a name of the one who makes an end (Rom. 10:4), of the termination of an action (Matt. 10:22; Mark 13:13; John 13:1; Luke 22:37; I Cor. 1:8; Heb. 3:14; 6:11; Rev. 2:26), of the last in a series (Rev. 21:6; 22:13), and of the purpose for which an action is done (II Cor. 1:13; Luke 18:5). It is used for the issue or outcome of an event (Matt. 26:58) or the result of action (Rom. 6:21) and the aim or the purpose of a thing (I Tim. 1:5).

It is also used as an adverb, translated as “Finally” (I Pet. 3:8; I Cor. 15:24). Hence the adjective teleios which is derived from this noun telos means the quality of having reach the end, that is, finished, complete. When used of persons, primarily of physical development, it means “full-grown, mature” (Heb. 5:14) and with respect to their moral (Phil. 3:15) and spiritual development (I Cor. 2:6; 14:20; Eph. 4:13), it means “mature”, in contrast to babes or infants [nepios]. Hence, it means “complete” and “perfect” in the sense of complete goodness, without reference either to maturity or the philosophical idea of perfection (Matt. 5:34; 19:21; James 1:4; 3:2).

Used of things, the Greek adjective teleios means “complete, perfect” (“the will of God”, Rom. 12:2; “work of endurance”, James 1:4; “law”, James 1:25; “gift from above”, James 1:17; “love”, I John 4:18) According to I Cor. 13:10, “when the perfect comes, the partial shall be abolished.” Hence, the perfect is the complete, not lacking of any part (compare, James 1:4 “lacking in nothing”).

The background of this meaning is in the Old Testament. In the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, the Septuagint (LXX), the word teleios usually translates the Hebrew word tamim, which occurs eighty-five times. Of these occurrences of the Hebrew word, fifty of them refer to sacrificial animals and is translated in our English versions “without blemish” or “without spot”. When applied to persons, the word describes one who is without moral blemish or defect (Psa. 101:2, 6; Job 1:1, 8; 2:3; 8:20, etc.). The term is also applied to God’s character and suggests a likeness between human persons and God, since man has been created in the image of God.

The English word “perfect” comes from the Latin perfectio meaning “completeness” or “completion.” The concept has been primarily applied to God, and then to man. As applied to man, perfectionism is the ethical theory that perfection is the end and goal of man.

The concept of perfection has a long history. It began in the sixth century B.C. among the Greek Eleatic philosophers.

Philosophically the concept of perfection has its origin implicitly in the teaching of the Greek philosopher Xenophanes (570-c.470 B.C.), who taught that God is a changeless being with the attributes of omnipresence and omniscience. Therefore, God does not move from place to place, and does not have any sense organs nor any physical form. God is unmoving, changeless, all-knowing, homogeneous, and ruler of all. He is the unity of the universe and its reality. This implied that change and movement in the universe are to some extant an illusion. He attacked the anthropomorphic Greek gods, and substituted in their place, “One god, the greatest among Gods and men, neither in form like unto mortals, nor in thought”, who “abideth ever in the self same place, moving not at all, nor doth it befit him to go about now hither now thither.” In his Metaphysics Aristotle tells us that Xenophanes, “referring to the whole world, said the One was god.” That is, Xenophanes was a monist, and not a monotheist, making him the forerunner of the Eleatic school of Greek philosophers.

Plato (428-348 B.C.) explicitly taught that God is a perfect being, and hence incapable of change, since change involved imperfection, changing from less perfect to more perfect, or vice versa. As the perfect being, God is the Good and the cause of good. This description of God as the Good relates God to the changeless realm of the Ideas, and separates God from the world of change. This gives to God the interpenetrating absolutes of Good, Truth, and Beauty. This unchanging perfection of God lead logically in later Platonism and Neoplatonism to the identification of God with the principle of unity: God is One. Since Plato thought of change as a quality foreign to Reason, the universal and the unchanging, this lead him to the view that man is a dualism of rational soul and body, the body as “the tomb of the soul”. Plato’s emphasis on the changelessness of the rational is seen in his claim that the soul is non-composite, hence simple. And since the soul is a simple entity (no parts), the soul cannot be destroyed, hence the soul is immortal.

Aristotle‘s (384-322 B.C.) analysis of perfection carried Plato’s concept of perfection as the unchanging to its completion and related it to the world of change. Aristotle analyzed change into the transition from the potential to the actual. He identified potentiality with the matter of a thing and actuality with the form of a thing. “Prime matter” is utterly formless potentiality for becoming a “this” or “that.” “Pure form” at the other extreme is pure actuality, without matter, without any potentiality, hence without any change. This pure changeless form is God. All other things are a composite of form and matter; they are the actuality of lower potentiality and the potentiality for higher actuality. God as this pure unchangeless form is perfect Being and every other things being both potentiality and actuality are imperfect. This perfect Being is pure actuality, without any change.

Aristotle does not make a radical dualism of mind and body that Plato does. In fact, for Aristotle the soul has a rational as well as irrational part. The rational part is the seat of intellect and it may be divided into an active and passive part. The active intellect which makes all things survives the body at death and is immortal. The passive intellect is the seat of appetites and desires. Man’s active intellect has no relation to desire, but his passive intellect can influence and exercise control of the desires. This occurs by the developments of habits, and leads to a moral will. Aristotle considers will as the actualization of desire. The appropriate development of man’s affective nature leads to moral virtue based on moral norms. On the other hand, the development of the active intellect leads to intellectual virtues of wisdom and insight. This wisdom (Sophia) is speculative and combines intuitive reason and rigorous knowledge of first causes and principles. Reason is the faculty of apprehending the universals and first principles in all knowledge. This knowledge depends upon sense perceptions but is not limited to the concrete and sensuous; it can grasp the universal and the ideal. The discipline of physics acquires this knowledge, and the wisdom and insight is best accomplished by the discipline of metaphysics (“after physics”). Aristotle’s Metaphysics is an example of the results of this discipline.

In terms of practical action, the virtuous life is the doing of the right thing in the right way to the right person to the right degree; that is, it involves the ability to find the mean between the extremes. The development of practical wisdom (phronesis) leads to the discovery of the Golden Mean. This mean lies between the extreme of deficiency and the extreme of excess. Aristotle remarks that the mean most often lies closer to excess than deficiency. As examples, courage, a virtuous state, lies between the deficiency of cowardice and the excess of foolhardiness. Temperance lies between insensibility and gluttony, friendship between obsequiousness and contentiousness, justice between the deficiency of letting one’s rights be trampled on and the excess of trampling on the rights of others. Following the mean in all things is human perfection.

Neoplatonism carries Plato’s concept of perfection as the unchanging in a different direction than Aristotle did. As the name suggests Neoplatonism starts from the philosophy of Plato, and interprets it a special way. This interpretation identifies God with the principle of unity, making God completely transcendent to the world of the many, but related to the world by a series of intermediaries, which are derived from the One by a principle of emanation. In this view reality is a graded series from the perfection of the One to the imperfection of the many of world. Man is a dualism of the divine and the material, who longs for union with the divine. This is the philosophy of the Egyptian-Roman philosopher Plotinus (A.D. 205-270). Plotinus attempts to explain how out of the One, the eternal principle of unity, the many of the intellectual and physical world could have arisen. The One is the undifferentiated divine out of whose being the other parts of reality are derived by emanation, which is logical and not temporal, that occurs due to the refulgence of the One. Plotinus identified three great levels of emanation from the One.

1. The first emanation is that of the Nous or Intelligence. This is Plato’s realm of the Ideas or forms. Plotinus interpreted the Nous as a multiplicity reflection of the unity of the eternal One.

2. The second emanation is that of the Psyche or World-Soul. This is the principle of life and active intelligence. It exists in contemplation of the Nous. It is like the demiurge of Plato by which the forms become the patterns of the material world. For Plotinus this World-Soul contains the world as its body.

3. The third emanation in the series is the Hyle or matter itself, which is devoid of form and is as such the closest approach to non-being. The evil in the world, and in man, is due to the privation of Being and the Good.

Whatever exists is an “overflow” of the One, and pervading all reality, at its different levels, and has an ardent longing for union with what is higher, and ultimately with the One itself. Thus in the human soul, fired by the heavenly Eros, the love of the perfect, of which Plato spoke in his Symposium, is driven to undertake an ascent to the One. According to Plotinus, man combines in himself the spiritual and material orders. In this position man is uncomfortable; he has a longing for the eternal forms of the Nous and for the perfect eternal One, and yet he is caught within an imperfect body. According to Plotinus, salvation is liberation from the multiplicity of the material to the unity of the rational and spiritual by means of contemplation, both intellectual and spiritual at once. The first stage of liberation is purification: the soul must free itself from the body and the beguilements of senses. At the second stage it rises to the level of Mind and occupies itself with philosophy and science, retaining his awareness of the self. The final stage is a mystical union with the One by means an ecstatic experience in which there occurs a lost of the awareness of the distinction between subject and object. This state of ecstasy is rarely, if ever, attained in this life and is usually short-lived. This liberation may take more than one lifetime.

Augustine (354-430 A.D.) accepted the Neoplatonic concept of perfection. He accepted the Neoplatonic concept of God’s being as One and unchanging but rejected the Neoplatonic theory of emanations; God is creator of the world out of nothing. With Neoplatonism, Augustine affirmed the perfection of the nature of God: His eternity, infinity, and incomprehensibility, His simplicity and unity, His essentiality without accidents. God is a being so different from all others that apparently contradictory statements can be true of Him simultaneously, that is, for example, He is eternal, timeless, yet containing all time, or in knowing His own Nature He can know the total future without depriving man of his freedom of choice. These statements that would be contradictory for any other beings than God’s Being, are true of God’s Being. But God’s Being transcends our understanding. This Neoplatonic concept of God’s Being was to become the standard for Christian theology for more than a thousand years after Augustine’s time.

Augustine also accepted the Neoplatonic concept that evil is a privation, the negation of the good. Anything insofar as it is, is good. So evil, being the negation of the good, is the lack of being. God as Being is the Good. To this concept of perfection Augustine added the concept of sinlessness. God as perfect Being never does anything that violates the law of His nature; He never sins because His nature is sinless. But man sins since the fall of Adam because his nature has been corrupted; man has a sinful nature and sins because of his sinful nature. The Greek conception of the imperfection of man’s being as subject to change (birth and death) had now become the imperfection of man’s sinful nature, “not able not to sin” (non posse non pecarre).

But this doctrine of human nature was opposed by the austere British “monk”, Pelagius (the question whether or not he was actually a monk has been raised, but his contemporaries referred to him as monachus). Sometime between A.D. 384 and 409, he had come to Rome and was teaching a view of human nature diametrically opposite to that taught by Augustine. By A.D. 397 Augustine was already putting forth his conception of mankind as a “lump of sin”, totally unable to save himself by good works because of his sinful nature, and wholly dependent upon God’s grace to enable him to do the good works necessary for salvation. Pelagius was primarily a moralist, and was concerned with right conduct. As a fashionable teacher at Rome, who exhorted his hearers to do good works, he was shocked when he heard Augustine’s prayer, “Give what Thou commandest, and command what Thou wilt” (da quod iubes et iube quod vis), for it seemed to suggest that man was incapable, apart from God’s grace, of doing good works to earn salvation. This was just the opposite of Pelagius’ whole system of ethics which was based upon the assumption of unconditional free will and responsibility. He held that God in creating man, unlike other creatures who were subject to the laws of nature, had given man the unique ability of being able to accomplish the divine will by his own choice. Pelagius rejected the idea that man’s will has any intrinsic bias toward wrong-doing as a result of the Fall of man. He believed that each soul is created immediately by God, and it cannot have come into the world tainted by original sin transmitted from Adam through its parents. Pelagius opposed the traducian theory that souls, like bodies, are generated from the parents, and thus have inherited from their parents a corrupt or sinful nature. Pelagius considered that this theory is tantamount to Manichaeism. He argued that if this theory is true, then the offspring of baptized parents would be free from the taint of original sin since baptism washed away the taint of original sin from the parents. Pelagius held that Adam’s trespass had disastrous consequences for human race; it introduced death, both physical and spiritual, into human race, and it set forth a habit of disobedience which was propagated, not by physical descent, but by custom and example. These wrong customs and bad example are overcome by God’s grace which was given at the soul’s creation; this grace of creation was

1. free will itself, or the possibility of not sinning which God endowed the soul at its creation; and

2. the revelation, through reason, of God’s law, instructing us what we should do and showing what would be consequences if we did not do those commands.

This grace overcomes the obscuring of the Law of Moses and the teaching and example of Christ through evil custom and bad example . This grace also bestowed forgiveness of sin in baptism and penance. But this grace of God does not bestow any special favor upon some, the elect, since God was no “acceptor of persons”. By merit alone men advances in perfection, and God’s predestination operates strictly in accordance with the quality of the lives that He foresees they will lead.

With these presuppositions Pelagius did not shrink from the logical implication that “a man can, if he will, observe God’s commandments without sinning”. He argued, Was it not written in the Bible, “Ye shall be holy, for I am holy” (Lev. 19:2), and “Be ye perfect, as your Father in heaven is perfect” (Matt. 5:49)? It would be impious to suggest that God, the Father of all justice, enjoins what He knows to be impossible. Thus Pelagius argued for the possibility of sinless perfection. Of course he recognized that some will not live such a life from childhood to death. But he envisage a state of perfection that could be attained by strenuous efforts of the will and which can be maintained only by steadily increasing application. Pelagius held that perfection was attainable in this life, otherwise, if it was not attainable, why did God command it?

For Augustine salvation by grace was an absolute necessity. Without God’s enablement, man cannot carry out the prescriptions of the law. The grace of God was not just an external aid to the keeping of the law that the Pelagians allowed. The grace of God must work internally, within us. It is an “internal and secret power, wonderful and ineffable”, by which God works in men’s heart. For Augustine the power of the grace of God is in effect the presence of the Holy Spirit. The letter of the law kills unless we have the life-giving Spirit to enable us to do what it prescribes. Augustine says, “It is the Spirit Who assists our infirmity.” For Augustine the Christian life was Spirit-empowered law-keeping. He distinguishes four kinds of grace.

a. There is “prevenient grace” (from Psa. 59:10: “His mercy goes before [in Latin, praevenient] me.”), by which God goes before and initiates in our souls whatever good we think or aspire to or will.

b. Then there is “co-operating grace”, by which God assists or co-operates with our will once it has been bestirred.

c. There is also “sufficient grace” (adiutorium sine quo), which is the grace which Adam possessed in Paradise and which placed him in the position, subject to his using his free will to the end, to practice and preserve in virtue.

d. Then there is also “efficient grace” (adiutorium quo), which is the grace granted to the saints predestined to God’s kingdom to enable them both to will and to do what God expects of them.

Grace of whatever kind is God’s free gift: gratia dei gratuita. The divine favor cannot be earn by good deeds of men for the simple reason that those deeds themselves are the effect of grace: “grace bestows merit, and is not bestowed in reward for them.” No good act can be performed without God’s help, and even the initial motions of faith are inspired in our heart by Him. This view of the grace of God led to Augustine view of predestination. Since grace takes the initiative and apart from it all men form a massa damnata, it is for God to determine who shall receive grace and who shall not. Augustine believed on the basis of Scripture that God has done this from all eternity. The number of the elect is strictly limited, being neither more than nor less than that required to replace the fallen angels. Then Augustine twisted the Scripture text, “God wills all men to be saved” (I Tim. 2:4) making it to mean that God wills the salvation of all the elect, among whom are men from every race and of every type. God’s choice of those to whom grace has been given in no way depends on God’s foreknowledge of their future merit. For whatever good deeds they will do will themselves be the fruit of grace. As far as foreknowledge is involved, what God foreknows is what He Himself is going to do. Then how does God decide to save this man rather than another? Augustine answers that can not be known by man since God has not revealed it. God will have mercy upon those whom He wishes to save and He will harden those upon whom He does not wish to have mercy. If this looks like favoritism, then let us remember that all are justly condemned. All are condemned because they all have sinned in Adam’s sin and because they all have personally sinned by the sinful nature they inherited from Adam. And that if any are saved at all, it is an act of ineffable compassion. This inscrutable decree is a mystery; man does not know who will be saved. Augustine was prepared to accept that certain people are predestined to eternal death and damnation; and they may include decent Christians who have been baptized, but have not received the grace of perseverance by which they will be enabled to finally earn eternal life. But Augustine spoke mostly of the predestination of the saints which consists of “God’s foreknowledge and preparation of the benefits by which those who are to be delivered are most assuredly delivered”. These alone have the grace of perseverance, and even before they are born they are sons of God and cannot perish.

Augustine response to Pelagius optimistic view of human nature that all men are able to obtain sinless perfection was a pessimistic view of human nature such that no man can obtain sinless perfection in this life, even if they receive the grace of perseverance. Only if the merits of the good works which grace enables them to do, outweighs the demerits of their sins, then that one will be rewarded with eternal life at the last judgment. Augustine denied that sinless perfection is obtainable in this life and it will only be the state of the elect in eternity. Even the elect still have a sinful nature until their physical death and it will only be removed in eternity.

Augustine accepted the Neoplatonic steps of salvation, but insisted that the grace of God makes it possible for man to ascend to God. To the problem of how man is to raise himself from the sense-world to the pure spirituality of God, Augustine proposed a three-fold mode of ascent: by the ladder of Virtue, of Speculation, and of Mysticism.

a. The ladder of Virtue is by human merit (meritum). But this merit can be earned by man’s good works only by the grace of God which enables him to do the good works. “When God crowns our merit, it is nothing but His own gifts that He crowns.” Grace is on the one hand that gift which man receives by grace, and on the other hand it is the “fulfilling of the law” and sum of all virtue. Therefore the ascent by Virtue or Merit is nothing more but ascent by the grace of God.

b. The ladder of Speculation is by human reason. God has made for us a ladder of created things by which we can mount up to Him. On the basis of Romans 1, Augustine worked out a complete Natural Theology (theologia naturalis). He held that God has arranged the universe as a great “order of nature”. By its aid, man can transverse His works from the lowest to the highest and so finally to reach the Creator Himself, to whom all these things point him. According to Plato, it is the beauty of things that arouses Eros in man and drives him to reach out longingly toward that which is in itself the Beautiful. Augustine also sees in the beauty of created things that leads us to look up their Creator and kindles our love for Him. At this point man must decide to turn his attention either downward to the corporeal world, or upward to God. Since God is not a corporeal being, man must choose to turn his attention upward, which is the right direction. If we are to find God, we must not seek Him here below in corporeal things but turn our attention upward, and ascend by meditation above everything that belongs to the corporeal world. But the ascent is not finished here even when we have transcended the corporeal world and reached the spiritual world. God is a spirit but not a mutable spirit. If we are to ascend to God, we also must not only ascend above the corporeal world, but also ascend above the world of mutable spirits. Augustine expresses this stage of the ladder of Speculation with the following command: “Transcend the body and taste the spirit; transcend the spirit and taste God.”

c. The ladder of Mysticism is ascent to God by means of a ecstatic union with God. The ladder of Speculation points in this direction, but this union cannot be reached by human reason, by one’s intellect. How is this union with God to be accomplished? Augustine’s answer is that man must find God within himself. Here Augustine enters upon the path advocated by all forms of mysticism in all ages, the introspective way to God. At the beginning of this road stands the sign, “Know thyself” (gnothi seauton). By entering into ourselves and examining one’s own nature, Augustine thinks that we can pierce through and into the mystery of the Holy Trinity. To know oneself is to know God; to abide in oneself is to abide in God. Following the injunction, Augustine finds three distinct elements within himself and within man in general: memory, understanding, and will. These are closely united, and are “of one and the same substance”, that is, they are “one essence”, nevertheless they are “three inasmuch as they are related to each other”, “not merely each to each but each to all… the whole of each is equal to the whole of each, and… to the whole of all together” (Trinity, x.18).

Though these ladders are similar to Neoplatonic way of salvation, Augustine is careful to distinguish these from it. Augustine is opposed to the view that the spirit of man is divine; man is not a disguised divinity. Augustine is very concerned to keep the distinction between God the Creator and man as His creature. God is God and man is man. Augustine is always conscious of the distance between God and man. He expressly rejects the interpretation of the Old Testament creation story of man, which makes it mean that God breathed into man part of His own divine Spirit. The spirit that God breathed into man was not God’s own spirit, but a created spirit. Augustine also rejects the Hellenistic interpretation of the goal of the third ladder is a mystical absorption of the human soul into God, where the distinction between God and man is abolished. The distinction between God and man is never abolished; even at the highest point of the Christians spiritual life, the distance between God and man is preserved. The goal of the Christian life is the dwelling of the Triune God in us, but “the Trinity is in us as God in His temple, but we are in Him as the creature of its Creator.”

Anselm (1033-1109 A.D.) made the ontological concept of perfection the basis of his ontological argument for the existence of God. God as perfect being, “that than which nothing greater can be conceived,” must necessarily exist because a perfect being would not be perfect if it did not exist. Anselm’s formulation of this argument in terms of that which “can be conceived” open his ontological argument to the criticism in Anselm’s time by Gaunilo, who claimed that on the same ground it can be argued that a perfect island must exist, since a perfect island can be conceived. Anselm answered this criticism by reformulating his argument without any reference to the conceiving of it.

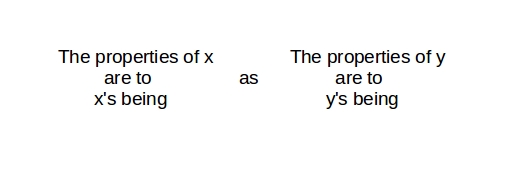

Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274 A.D.) argued from the grades of perfection in the world that God as a perfect Being existed. In experience we recognize degrees of truth, goodness. In order for our judgments of this sort to be meaningful there must exist in a supreme way truth, goodness, thus perfection. Thus there must be a Supreme Being who is truth, goodness, and perfection. Aquinas called these supreme concepts “transcendentals”, terms that go beyond any genus, and apply to everything that is; they are attributes of everything. He identified six of these transcendentals: ens, res, unum, aliquid, verum, bonum (being, thing, unity, distinction, true, good). All beings ens are things (res) with unity (unum), distinguished (aliquid) from what is not themselves. All things are what they are, hence in relation to knowledge, are true (verum). And all things tend toward their ends, or goals which is their good (bonum). These six transcendentals define the concept of perfection. These transcendentals are applied to God by the principle of analogy to determine God’s nature. The analogy that Thomas used is the analogy of proportionality, which can be expressed as follows:

When applied to God’s being, we are led to expect that in the measure as God’s being exceeds ours so will the properties of His being exceeds ours. In relating God’s Being to the transcendentals we gain other properties: eternity or timelessness, omnipresence, omniscience, omnipotence, etc. From all of this emerges the classical concept of a perfect being that is the synthesis of ideas of Plato, Aristotle, Augustine. God is perfect being, unchanging, utterly simple and unitary, hence indestructible, absolute truth and goodness, not dependent on the world, yet everything in the world is dependent on God.

Regarding man’s soul, Aquinas following Aristotle distinguishes between the intellectual, volitional, and appetitive functions therein. When considering the goods that satisfy the senses, the appetite is said to be concupisciple, and the passions related to this function include love, desire, delight, hate, aversion, and sorrow. When considering the goods that satisfy the intellect, called the rational appetite (or will), a second kind of love relates to this function of the soul. The function of the intellect is to understand, and includes apprehension, judgment, and reasoning. The intellect abstracts universal meaning from sense experience by means of phantasms standing for the species of the perceived things. For Aquinas this requires the division of intellect into two functions: the passive intellect (intellectus possibilis) which receives the phantasms, and the active intellect (intellectus agens) which grasps the abstracted meaning.

Aquinas follows quite closely Aristotle’s ethical theory. But to the virtues gained by the Aristotelian analysis there must be added and complemented by the “theological” virtues of faith, hope, and love, justifying grace being the basis. Thus Aquinas follows a natural law ethics or an ethics of natural reason. The basic principle of this ethics is that good should be done and evil avoided. Law is “an ordinance of reason promulgated for the common good.” Right action is an action which “precedes to its end in accord with the order of reason and of eternal law.” Thus the concept of the “right” emerges from the notion of “good” through the medium of order and law. Ethics rests on the principles of practical reason where science rests on the principles of theoretical reason. Prudence, that is, right reason about things that must be done, likewise rests on the practical reason.

The same kind of law that directs man with respect to right and wrong in daily life, directs man with respect to the common good of society. This law is called natural law or jus naturale. Just as there are laws implanted in physical nature, which are natural laws, so there are laws implanted by the Creator in human nature and discernible by man’s reason. The only difference between these laws is that man is able to disobey the moral laws of his nature.

Aquinas distinguishes four interrelated types of law: the divine or eternal law, natural law, the law of nations, and positive or civil law. For Aquinas the basis of all law is jus divinum, or eternal law in the mind of God. This law is given to man in part by revelation and another part of it is implanted in man, and is available through the use of human reason. This is natural law or jus naturale. This natural law finds expression in the two further types of law: civil law or jus civile, and the law of the nations or jus gentium. Civil law is the set of laws governing a particular society. Aquinas finds that since societies differ from each other and are in different situations, the precepts of natural law must be particularized to fit the contingent circumstances of each society. The law of nations is a set of laws on which all societies agree. It would be a body of international law. This set of laws could also be drawn from natural law; but its determination is by way of deduction, as conclusion drawn from premises.

In his theology of salvation, Aquinas followed Augustine’s theology of grace. But in his interpretation of original sin Aquinas believed that Adam lost his original righteousness and the result in all men is a disordered disposition. All Adam’s descendants lack this original righteousness but the nature of man is not changed, and the natural inclination to virtue is diminished. Original sin is a disordered disposition due to the lack of this original righteousness. Actual sins, which are to be distinguished from original sin, vary from person to person in both nature and extent. Both original and actual sins cause weakness and ignorance; all powers of the soul are “left to some extent destitute of their proper order”. Sin also results in physical death. In the view of Aquinas physical death is not natural to man. The corruptible body of man God has adapted to its form, the rational soul of man, and to its end, eternal happiness.

Thomas Aquinas adopted as did Medieval theology the three ladders of Augustine. Medieval theology thought it self-evident that if man is be saved he would have to ascend to God’s level. The salvation of the soul is its ascent from the imperfect world to the perfection of God. And there are, in particular, three ladders to heaven for the soul’s ascent: (1) the ladder of Merit; (2) the analogical ladder of Speculation; (3) the anagogical ladder of Mysticism.

a. The ladder of Merit is not opposed to grace. Medieval theology is a theology of merit; but this does not mean it is not a theology of grace. The New Testament (particularly the writings of Apostle Paul) and the Reformation saw these as opposed to each other. But Medieval theology since the time of Augustine saw these as complementary if not one. The way to God and blessedness is by means of human merit. As Thomas Aquinas writes, “Man attains blessedness by a series of acts which are called merits.” But this does not exclude Divine grace or make salvation by man alone. On the contrary, Aquinas most emphatically rejects the idea that man might acquire blessedness by his own strength. For Aquinas there is not a contradiction between the idea of merits and the idea of grace; each is the condition of the other and they are complementary. Merit is required of man, but he cannot achieve this merit apart from the Divine grace and unless Divine grace comes to his aid: without grace no merit. This is generally true of Medieval theology and it had its origin in the theology of Augustine and faithfully upholds the Augustine principle: “When God crowns our merit, it is nothing but His own gifts that He crowns.”

b. The analogical ladder of Speculation is the specific form that the ladder of speculation took in the theology of Aquinas. By the ladder of religious speculation, since the time of Augustine, Medieval theology has ascended from the world of sense to the spiritual world of God. The relation between the world and God was primarily conceived upon the principle of causality, that for every effect of a change there is adequate cause. Since God is “the first and the universal Cause of all being”, it is possible to find in everything, in so far as it is a being, likenesses to God. It is the task of theology to find these Divine “traces” in the universe and to rise by their aid to a contemplation of God Himself in His majesty. Of course, within the created world there is no absolute likeness to God. But everywhere in creation, from the lowest to highest, there are analogies to the Divine Being, clearer at higher, fainter at the lower levels. By observing these analogies and working back from the effect to the first cause (via causalitatus), by negating the imperfect (via negationis), and positing the perfect (via eminentiae) which the effect implies, one can reach a true, never exhaustive, but adequate knowledge of the nature of God.

c. The anagogical ladder of Mysticism is the way of inner ascent [anagoge] to union with the Divine. In the soul of man there are those divine and uncreated elements. These are the peaks that the soul must climb if he is come in contact with God. The mystic seeks the point within himself where he can make contact with God. It is the Neoplatonic One [hen] in man, which makes possible unity [henosis] with the One divine Being [to theion hen]. But this height is not reached without thorough preparation. Here the old ordo salutis of mysticism, with its three steps of purification, illumination and union, must be used. Medieval mysticism made reference to Christ’s ascension as a pattern for the ascent of the soul. This is expressed clearly by Bernard of Claivaux, who says:

“When our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ wished to teach us how we might ascend to heaven, He Himself did what He taught: He first descended, and as His simple divine nature, which can neither lessened nor increased nor undergo any other change, did not permit Him either to descend or ascend, He took up into the unity of His person our nature — that is, human nature. In this He descended and ascended and showed us the way by which we, too, might ascend.”

Bernard sees in the upright form given to man at creation an evidence that he is meant by God to direct his desire upward. But the natural man in his attempt to raise himself up, takes a false path of pride and presumption, and sinks even deeper down. He can only be rescued when Christ shows him the right way. We are called to be followers of Christ. In this life we are to follow Him in lowliness and humiliation. But that is not all. Our “Imitatio Christi” [Imitation of Christ] is to include both humiliation and exaltation. We are to follow Christ in everything, not only when He descends in His Incarnation, but also when at His Ascension He ascends into heaven. To both Bernard applies the words of Jesus in Luke 10:37: “Go, and do thou likewise.” On these lines Bernard interprets the Sermon on the Mount. The eight Beatitudes signify eight rungs on the mystical heavenly ladder, whose foot is here below while its top reaches up to heaven. On this ladder we must ascend above ourselves and above everything in the world. Only then can our spirit reach the higher world and come to full and immediate union with God. But during this life, this highest happiness is granted to man in isolated and fleeting moments.

Aquinas believed that final perfection and the beatific vision of God was reserved for the life to come after death, but in this life he believed that by contemplation a perfect vision of God and a perfect knowledge of the truth could be had. For Aquinas perfection involved the disparagement of the world and the desires of the flesh, which he considered the source of evil. Elimination of bodily desires was a prerequisite for obtaining perfection; thus perfection was for Aquinas renunciation. Associated with the obtaining of this perfection was human merit; to obtain perfection one had to do good works by which to acquire merit that would be rewarded in the after life with the beatific vision of God. For those imperfect there was a treasury of merits of the saints from which the imperfect could draw at the discretion of the Church. In order to obtain perfection Aquinas set up a hierarchy of states of perfection to which corresponded the levels of the religious orders. Although he did not deny the possibility of perfection for all persons, he believed that religious vows were certainly a meritorious aid to perfection. He thus perpetuated the spiritual dichotomy between clergy and laity.

The Reformers, both Lutheran and Calvinist, rejected the three ladders, the ladders of Merit, of Speculation, of Union, by which one could obtain perfection. But they retained the Augustinian understanding of man as having a sinful nature and that consequently man cannot obtain perfection in this life. This original sin remains with man until death, even in those who are declared righteous by the imputation of Christ’s merits through faith. These believers are regenerated receiving a new nature, but the old nature is still there in the believer. The experience of chapter 7 of Romans is interpreted as the conflict between these two natures. The Christian life is characterized as struggle with the sinful nature to keep it under control, subject to God’s law. Because of this sinful nature, spiritual perfection is impossible in this life. Lutheran theology saw the believer both simultaneously a saint and sinner. Calvin says that while the goal toward which the pious strive was to appear before God without spot or blemish, the believer will never reach that goal until the sinful physical body is laid aside in death. He saw the physical body as the residence of the depravity of concupiscence. Thus perfection and the physical body are mutually exclusive.

Luther saw the sinful nature expressed in man’s ego-centric love of the self. This stands in contrast to real love which is other centered, does not seek its own, but gives and sacrifices itself. This is the love that God has for man and was demonstrated in the incarnation, sufferings and death of Jesus Christ for all men. This perfect love is the perfection that Jesus commanded in His Sermon on the Mount, “Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect” (Matt. 5:48). Thus perfect love stand in contrast with human love which is centered on the human self. Man loves because of the benefit that this love gives himself. Man loves the lovable. Luther brands selfishness, self-love, as sin and as the essence of the sinfulness of sin. He knows no acceptable self-love. The commandment: “Thou shalt love your neighbor as thyself”, Luther interpreted, not as approving of love of self, but as a rejection and condemnation of all self-love whatsoever. He rejects Augustine’s interpretation that this command is actually a commandment to love one’s self. On the basis of John 12:25: “He who loves his life loses it, and he who hates his life in this world will keep it for eternal life”, Luther puts forth the fundamental principle: “To love is the same as to hate one’s self.” Luther states this principle in direct opposition to the universally accept axiom that “ordered love begin with oneself”, and the immense authority of Augustine. According to Luther this one idea has done most to lead away from real love. In commanding man to love his neighbor as himself, God has in no way commanded man to love himself. Self-love is a vicious love [“vitiosus amor“] that must be destroyed. But it can serve as a pattern for the right kind of love to our neighbor, but not as a command to love one’s self nor as approving of self-love. Luther sees this self-love as essence of the sinful nature. Real love, God’s love, is other centered. “Love seeketh not its own.” Sin is the opposite of this; the essence of sin is that man seeks its own. By this standard, the whole of human life is under the dominion of sin. And since this a universal character of man, sin is completely universal in its extent. Sin has its seat, not just in man’s sensible nature, but it embraces the whole of man. This means that all of the acts of man, no matter how great and praiseworthy the act, is penetrated by sin and sin is inherent in everything human. God alone in His love is totally other-centered and seeketh not His own. This is the perfection of God and the perfection that God has commanded and that man should seek. True perfection does not consist in celibacy or mendicancy. Luther rejected the distinction between clerical and lay perfection, and stressed that correct ethical behavior is not found in renunciation of life, but in selfless love of one’s neighbor.

Toward the end of the seventeenth century in Lutheran German church, there arose a movement that came to be known as pietism. The movement arose in protest to the cold and sterility of the established church forms and practice. Many ministers seemed to be more interested in theological and philosophical wrangling and rhetorical disputation than in the exhortation and encouragement of their congregations. And the devastating Thirty Years War (1618-1648) fought between the Lutheran and Roman Catholic states of Germany had created a dissatisfaction with the Lutheran church’s involvement in political and military matters. There was also a dissatisfaction with the formalism and deadness of the church and the insincerity of the church leaders. There arose a call for reform, some from outside of Germany from Calvinistic Holland and Puritan England. Within the German-speaking reformers, the call for reform in the writings of such men as Johann Arndt, whose True Christianity (1610) strongly influenced the later leaders of pietism.

It was the work of Philipp Jakob Spener (1635-1705), often known as the father of pietism, that began the movement known as pietism. He was born in Rappoltsweiler, Upper Alsace, and died in Berlin. He received a strict, pious upbringing and took his university training in Strasborg (1651-1659), where he concentrated on Biblical languages and historical studies. The professors at Strasborg stressed spiritual rebirth and ethical concerns, which became important factors later in Spener’s preaching. After graduation he served in pastoral positions in Strasborg (1663), Frankfort-on-Main (1666), Dresden (1686), and Berlin (1697). When he was called to be senior minister in Frankfort-on-Main, he called for reform in the city. He had initiated a far-flung correspondence which eventually won him the title of “spiritual counselor of all Germany”. He thus promoted a major reform in the practical life of the churches. In a sermon preached in 1669, Spener mentioned the possibility of laymen meeting together, setting aside “glasses, cards, or dice”, and encouraging each other in the Christian faith. The next year Spener himself instituted such meetings which he called a collegia prietatis [“pious assembly”] to meet on Wednesday and Sunday evenings to pray and discuss the previous Sunday’s sermon, and to apply passages of Scripture and devotional writings to their individual lives. From his name of these meetings the name of the movement, pietism, was derived. In 1675 Spener took a major step toward reviving the church when he was asked to prepare a new preface for the collection of sermons of Johann Arndt. The result was the famous tract Pia Desideria [“Pious Wishes”], in which Spener examines the sources of spiritual decline in Protestant Germany and offered proposals for reform. This tract was an immediate sensation. In it Spener criticized the nobles and princes for exercising unauthorized control of the church, ministers for substituting cold doctrine for warm faith, and lay people for disregarding proper Christian behavior. Positively, he called for a revival of the concerns of Luther and the early Reformation, even altering slightly Reformation teachings. For example, Spener regarded salvation more as regeneration (new birth) than justification by the imputed righteousness of Christ, even though the Reformers laid greater emphasis on the latter.

Spener offered in his Pia Desideria six proposals for reform, which became a short summary of pietism.

a. There should be “a more extensive use of the Word of God among us”. The Bible, Spener said, “must be the chief means for reforming something.”

b. There should be a renewal of “the spiritual priesthood”, that is, the priesthood of all believers. Here he cited Luther’s example in urging all Christians to be active in the general work of the ministry.

c. There should be a seriousness about holy living and that more time should be spent in following God’s law, spreading the gospel, and providing aid for the needy. Spener argued that Christianity is more than a simple knowledge; Christians should practice what they believed.

d. There should be more restraint and charity in religious controversies. Spener asked his readers to love and pray for unbelievers and the erring, and adopt a moderate tone in disputes.

e. There should be a reform in the education of ministers. Spener urged that there be a stress on a training in piety as well as on academic subjects.

f. Lastly, ministers should preach edifying sermons, understandable to people, rather than technical theological discourses in which few were interested and could even understand.

These proposal for reform and renewal ran into two major difficulties.

a. First, many clergymen and professional theologians opposed them, some out of concern for their traditional status, but others out of a genuine fear they would lead to rampant subjectivism and anti-intellectualism.

b. Second, some lay people took Spener’s proposals as permission to leave the established church completely, and start their own churches. Spener himself opposed these separatist conclusions drawn from his proposals.

Spener left Frankfort in 1686 for Dresden and from there he was called to Berlin in 1691. His time in Dresden was marked by controversy. But while he was in Dresden he met his successor, August Hermann Francke. In Berlin Spener helped to found the University of Halle, to which Francke was called in 1692. Under Francke’s leadership the University of Halle showed what pietism could mean when put into practice. Very quickly, Francke opened his own home as a school for poor children, he founded a world-famous orphanage, he established an institute for training teachers, and later he helped found a publishing house, a medical clinic, and other institutions.

Francke had experienced a dramatic conversion in 1687, which was source of his lifelong concern in evangelism and missions. Under his leadership Halle became the center of Protestantism’s most ambitious missionary endeavors up to that time. The university established a center for Oriental languages and also encouraged the translation of the Bible into new languages. Francke’s missionary influence was felt directly through the missionaries who went from Halle to the foreign fields and indirectly through groups like the Moravians and an active Danish mission which drew inspiration from the leaders of pietism.

Spener and Francke inspired other varieties of German pietism. The head of the renewed Moravian Church, Count Nikolas von Zinzendorf, was Spener’s godson and Francke’s pupil. Zinzendorf organized refugees from Moravia into a kind of collegia pietatis, within German Lutheranism, and later shepherded this group in reviving the Bohemian Unity of the Brethren. These Moravians, as they were later called, carried the pietistic concern for personal spirituality almost literally around the world. It was a group of Moravian missionaries that John Wesley met during his voyage to Georgia in 1735. Wesley was so impressed by their behavior then and what he heard of their faith that after returning to England he was led to his own evangelical awakening.

The pietists rejected the pessimism which the Lutherans and Calvinists viewed the quest for perfection. Pietism was marked by the quest for personal holiness and by an emphasis on spiritual devotion rather than doctrine by such leaders as Spener and Francke, who stressed personal holiness marked by love and obedience. But some of the fears of its earliest opponents that pietism could lead to subjectivism and emotionalism; that it would discourage scholarship and intellectual pursuits, that it could fragment the church through its separatism; that it could establish new codes of legalistic morality; and that it could underrate the value of Christian tradition, have taken place.

George Fox (1624-1691), the founder the Society of Friends, better known as the Quakers, in 1647 had a profound religious experience that changed the direction of his life. Later in 1652 he relates that he had a vision at a place called Pendle Hill, and from that point on he based his faith on the concept that God could speak directly to any person. He began to preach that the truth is to be found in God’s voice speaking to the soul; those who listen to God’s voice, Fox called the “Friends of Truth”, later shortened to just “Friends”. In 1649 he was arrested and jailed for interrupting a Nottingham church service with an impassioned appeal from the Scripture to the Spirit as the authority and guide. In 1650 he was imprisoned as a blasphemer, and at the trial the judge, Justice Bennet of Derby, nicknamed the group “Quakers” after Fox exhorted the magistrate to “tremble at the Word of God”. Fox later describes the church service where the term was used;

“The priest scoffed at us and called us Quakers. but the Lord’s power was so over them, and the word of life was declared with such authority and dread to them, that the priest began trembling himself; and one of people said, ‘Look how the priest trembles and shakes, he is turned a Quaker also’.”

Fox was born at Leicestershire and was apprenticed to a shoemaker. He apparently had no formal schooling. In 1643 he left his family and friends in search of enlightenment. After a painful search, he came to rely on what he called the “Inner light of the living Christ”.

Fox taught both personal responsibility for faith and freedom from sin in his doctrine of the inner light. He declared a doctrine of real holiness rather than imputed righteousness. Fox believed that as a result of the new birth into Christ by the Spirit, the believer was freed from actual sinning, which he defined as transgression of the law of God, and is thus perfect obedience to God. This perfection is relative in that it dealt with victory over sin rather than absolute moral development. But this perfection did not remove the possibility of sinning, for the Christian must needs constantly to rely on the inner light and must focus on Christ as the center of faith. Fox contended that the Christian is restored to the innocency of Adam before the fall. Not all later Quakers agreed with him on this point. Fox emphasized that center of perfection was in the cross of Christ. The cross was no dead relic but was an inner experience that changed the believer into perfect love. Fox refused to be preoccupied with sin as the Puritans were with their pessimism over the profound sinfulness of man. Fox also distrusted all external means of grace such as the sacraments. The meeting of the believers had no ritual and was a waiting in silence upon God, for the Spirit to speak in and through them. The “Inner Light” was as important as the Scriptures; sacraments, ceremonies, and clergy was abandoned.

To continue, click here.