book_d2lsyn

SYNOPSIS

by Ray Shelton

Two days before my first daughter Barbara’s birth and on my first son Stephen’s first birthday, October 14, 1952, there occurred an event that changed my understanding of salvation and the whole direction of my study for the ministry. On that day, while I setting in Dr. Carnell’s class in Systematic Theology at Fuller Seminary, while he was lecturing on the doctrine of original sin, he focused our attention on the Rom. 5:12 as the Scriptural basis of that doctrine.

“Therefore as sin came into the world through one man and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all men sinned –” (Rom. 5:12 RSV)

I opened my Greek New Testament and began to read what the Apostle Paul wrote. As I got to the last clause of the verse, I notice something that I had not noticed before (I had had three courses in college that studied the book of Romans; at BJU, a course in the Pauline Epistles and the first semester of the third year Greek course, in which we read Romans in Greek, and at Wheaton a course in Romans). I saw there a relative pronoun that was not translated in our English translations. If it were translated into English, then the last clause should read, “because of which all sinned”, not “because all sinned”. The English translation “because all men sinned” in RSV and in other modern translations is incomplete, if not wrong and misleading. These translations makes Paul appear to contradict what he says in this verse and in the next two verse; that is, it made Paul appear to say death spread unto all men because of their sins instead of Adam’s sin. Paul clearly says in Rom. 5:12 that death spread unto all men because of Adam’s sin. And in the next two verses Paul clearly says that death reigned between Adam and Moses over those who had not sinned after the likeness of Adam’s transgression. Between Adam and Moses there was no law that made death the consequence of their personal transgressions.

“13 sin indeed was in the world before the law was given, but sin is not counted where there is no law. 14 Yet death reigned from Adam to Moses, even over those whose sins were not like the transgression of Adam, who was a type of the one who was to come.” (Rom. 5:13-14 RSV)

But if the relative pronoun is translated the inconsistency is removed. In the Greek, the relative pronoun clearly refers back to the word “death” in the previous clause; that is, “because of death all sinned.” The death that spread unto all men as the result of Adam’s sin was the condition or the reason why all men sinned. That is, all men sinned because of death.

“Therefore, as through one man sin entered into the world, and death through sin, and so death passed unto all men, because of which [death] all sinned:–” (Rom. 5:12 ERS)

But how is that possible? How can all men sin because of death? Then I remembered what I had been taught that death is separation and that there are three kinds of death;

1. physical death which is the separation men’s spirit from their body when they physically dies,

2. spiritual death which is the separation of men’s spirit from God, and

3..eternal death which is the eternal separation of men from God.

The death that spread unto all men from Adam’s sin is physical and spiritual death. All men are born spiritually dead and are going to die physically. It is this spiritual death that is the condition or ground for all men sinning. But how can men sin because of spiritual death? What is sin? I had ask this very question to the Lord several weeks before. And as I was reading an article in the theological journal, Theology Today, titled “Biblical Metaphysic and Christian Philosophy” (October 1952, pp. 360-375), by E. LaB. Cherbonnier, I got the answer. In his analysis of human freedom in this article (p. 367), Cherbonnier concluded that every man must have a god. By the very constitution of his freedom man must have an ultimate criterion of decision. That is, behind every decision as to which thing a man should do or think, there is a reason, a criterion of decision. And the ultimate reason for any decision, practical or theoretical, must be given in terms of some particular criterion, an ultimate reference or orientation point in or beyond the self or person making the decision. This ultimate criterion is that person’s god.

I saw that every man must then choose something as his god. If he doesn’t choose the true God as his ultimate criterion of decision, he will choose a false god. He will choose some part or aspect of reality as his god, deifying it. “They exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshipped and served the creature rather than the Creator.” (Rom. 1:25) The choice of a false god and the consequent personal allegiance and devotion to it is what the Bible calls idolatry. An idol does not have to be an image of wood, stone, or metal. It may be money, wealth, power, pleasure, education, the family, mankind, the state, democracy, experience, reason, science, the moral law, etc. An idol is a false god, and a false god may be anything, which may be good in its proper place, that takes the place of the true God, anything a person chooses as his or her ultimate criterion of decision, exalting it as God. It is any substitute or replacement for the true God in a person’s life.

Since a false god usurps the place of the true God in a person’s life, idolatry is the basic sin. This sin is directly against the true God; it is a direct insult to Him and an affront to His divine majesty. No more serious sin could be imagined than this one. Since it is the most serious sin, it is therefore the most basic. This is the main reason that idolatry is the first sin prohibited by the Ten Commandments. “Thou shalt have no other gods besides me.” (Exodus 20:3) Thus idolatry is the basic sin, not pride; pride is not even mentioned in the Ten Commandments. Idolatry is also the basic sin because this sin leads to other sins. It leads to other sins since a person’s god, being his ultimate criterion of decision, will determine the choices he or she will make. The choice of a wrong god will lead to other wrong choices. That is, the idol that a person sets up in his heart (Ezek. 14:35) will affect the character and quality of his whole life. Idolatry is therefore the basic sin.

Now I could understand how death leads to sin. If a man is spiritually dead, separated from the true God, and since he must choose a god, he will usually choose a false god. Thus all men sin because of death. As I was sitting there in the class thinking about this, another passage of Scripture occurred to me — Gal. 4:8, “Formerly, when you did not know God, you were in bondage to beings that by nature are no gods.” Not to “know God” personally as a living reality is to be spiritually dead; spiritual death is the opposite of spiritual or eternal life which is to know the true God and Jesus Christ whom He sent (Compare John 17:3, where Jesus said as He prayed: “And this is eternal life, that they know Thee, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom Thou hast sent.”).

And a person is “in bondage to beings that are no gods” when he chooses them as his gods. He chooses them because he does not know personally the true God, that is, because he does not have life, because he is spiritually dead. The true God is not a living reality to him. And lacking this personal knowledge of the true God as a living reality, a person does not have the reason for choosing the true God as his ultimate criterion of decision. God Himself is the only adequate reason for choosing Him. He cannot be chosen for any other reason than Himself. For then He would not be God but rather that reason for which He is chosen would be god to that person. Only a living encounter with the true and living God can produce the situation in which God Himself may be chosen. God Himself is the only condition for the choice of Himself by a person. Thus apart from a personal revelation of God Himself, a person will usually choose as his god that which seems like God to him from among the creation around him or from the creations of his own hands or mind. Man does not necessarily have to sin, but he usually will. Spiritual death is not the necessary cause of sin but the basis or condition of the choice of a false god. (The Greek word translated “because” in the last clause of Rom. 5:12 means “on the basis of” or “on the condition of.”)

Man is not responsible for becoming spiritually dead because he did not choose this state. He inherited spiritual death from Adam just as he inherited physical death, but not eternal death. But he is responsible for the god he has chosen. The true God has not left man without a knowledge about Himself (Rom. 1:19-20). This knowledge about God leaves man without an excuse for his idolatry, but it does not save him because it is a knowledge about the true God and not a personal knowledge of the true God, a personal relationship to God. Even though a person is not responsible for becoming spiritually dead, he is responsible for remaining in the state of spiritual death when deliverance from it is offered to him in the person of Jesus Christ. If he refuses the gift of eternal life in Christ Jesus, he will receive the results of his decision, eternal death. “For the wages of sin is death, but the gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.” (Rom. 6:23)

If a man refuses the gift of spiritual and eternal life in Christ Jesus and continues to put his trust in a false god, remaining in spiritual death, then after he dies physically, at the last judgment he will receive the result of his decision, eternal death, eternal separation from God.

This relationship between death and sin opened for me a whole new understanding of salvation. Spiritual death is not the result of a man’s own personal sins. On the contrary, man sins because he is spiritually dead. That is why he needs to be saved. He is dead spiritually and dying physically. He needs life; he needs to be made alive — he needs to be raised from the dead. And if he receives spiritual life, if he is made alive to God, then death which leads to sin will be removed and man can be saved from sin. Thus salvation must be understood to be primarily from death and secondarily from sin. Salvation is primarily deliverance from death to life, reconciliation to God, and secondarily from sin to righteousness, redemption from the slavery of sin.

Now God has accomplished this salvation from death to life through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, His Son. God in His love for us sent His Son to enter into our death so that He might deliver us from death. On the cross Jesus died not only physically but spiritually.

“My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” (Matt. 27:46)

He was forsaken for us; He died for us. He tasted death for every man (Heb. 2:9). But God raised Him from the dead. Jesus entered into our death in order that as He was raised from the dead, we might be made alive in and with Him (Eph. 2:5). Hence Christ’s death is our death, and His resurrection is our resurrection. We who have accepted Him are made alive with Him and in Him. In my book, From Death To Life, I examine in greater detail the implications of this discovery for the understanding of the Biblical doctrine of salvation.

1. First, I examined in chapter 1 the Biblical doctrine of sin and death to show the need for salvation. There it was shown that man needs to be saved from death, sin and wrath; that the basic sin is idolatry and that man sins because he is spiritually dead.

2. In chapter 2, I examined the Biblical doctrine of salvation by the grace of God. There it was shown that salvation is basically from death to life and then from sin to righteousness and from wrath to peace with God. This lead to a discussion of the Biblical doctrines of the righteousness of God and justification by faith.

3. Then in chapter 3, I examined the Biblical doctrine of covenants of God in order to correctly understand the law of God and the distortion and misunderstanding of the law of God called legalism.

4. In chapter 4, I showed how legalism has caused in Christian theology a misunderstanding and distortion of the Biblical doctrine of the need for salvation.

5. In chapter 5, I showed how in Christian theology this Biblical doctrine of salvation has also been misunderstood because of legalism.

6. This lead to an examination in chapter 6 of the central problem of Christian theology — the problem of the atonement: why did Christ have to die?

7. Finally, in chapter 7, I examined the Biblical doctrine of the Christian life as the present tense of salvation and the problems that the legalistic misunderstanding of salvation has caused in the Christian life.

From the examination of the Biblical doctrine of sin and death in Chapter 1 of my book, From Death to Life, it became clear that man needs to be saved because man is spiritually dead. Man is separated and alienated from God. He does not know God, and because he does not know the true God, he turns to false gods — that which is not God — and makes these into his gods (Gal. 4:8). Man’s basic sin is idolatry — trust in a false god, and he sins (chooses these false gods) because he is spiritually dead — separated from the true God (“because of which [death] all sinned,” Rom. 5:12d ERS). This separation is not the result of a man’s own personal sins. He received this spiritual death, along with physical death, from Adam, from his first parents. What is the origin of sin? The Biblical answer is twofold:

(a) sin had its historical origin in the act of Adam which is called the fall, and

(b) sin has its immediate, contemporary and personal origin in the spiritual death which along with physical death spread upon the whole race because of Adam’s act of sin.

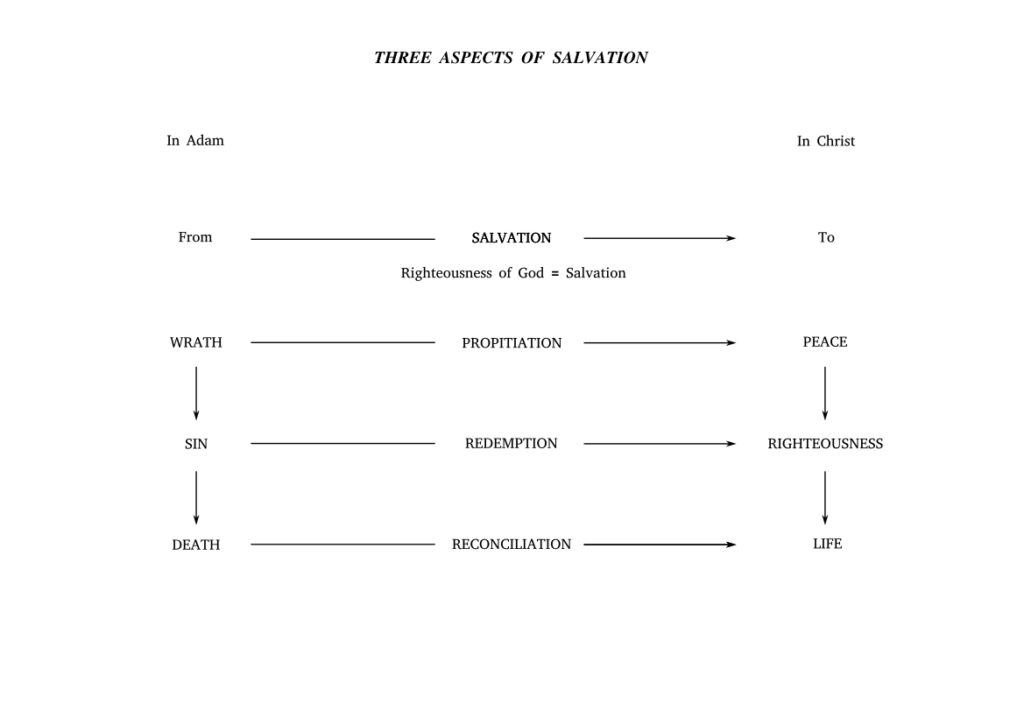

The classical passage of Scripture that sets forth this twofold origin of sin is Romans 5:12. The historical origin of sin is the fall of Adam — the sin of the first man. Adam’s sin brought death, and this death has been spread throughout the whole human race, to all Adam’s descendants (Rom. 5:12). This is why man needs to be saved. He is dead spiritually and dying physically. He needs life — he needs to be made alive — to be raised from the dead. This spiritual death inherited from Adam is the personal, contemporary origin of each man’s sin. This is what the last phrase of Rom. 5:12 says; “because of which [death] all sinned.” And if he receives life, if he is made alive to God, man will then be saved from sin. By removing the cause of sin — spiritual death — by giving him spiritual life, God delivers man from sin. For just as sin flows from death, so righteousness — trust in the true God — flows from life. Salvation is primarily from death and then secondarily from sin. And since God’s wrath — God’s opposition to sin — is caused by sin (Rom. 1:18), the removal of sin brings with it also the removal of wrath. Salvation is then also from wrath (Rom. 5:1). Propitiation is the scarifical aspect of salvation from wrath to peace. Redemption is the liberation aspect of salvation from sin to righteousness. Reconciliation is the representative aspect of salvation from death to life. And salvation is a propitiation because it is a redemption and it is a redemption because it is a reconciliation to God. In propitiation, wrath, being caused by sin, is removed and in redemption, sin, being caused by death, is removed and in reconciliation, being made alive, death is removed. Propitiation, Redemption, and Reconciliation are the three aspects of salvation.

These three aspects of the salvation was accomplished for us through the death and resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ.

In chapter 2, we saw that this salvation is exactly what God accomplished through the death and resurrection of Jesus, His Son. God in the person of His Son entered into our death so that He might deliver us from death by raising Jesus from the dead. His resurrection is our resurrection, and we are made alive with Him and in Him. Thus taking away the cause of our sin, He saves us from sin. Jesus died for our sins — literally — to take them away, not just the guilt of sin but sin itself. For, being made alive to God with Christ, we now in faith trust in the true God. This faith in God is the opposite of sin, which is trust in a false god. We have turned from our false gods to serve and trust the true God that we now know. This faith is righteousness (Rom. 4:3, 5), and it comes from knowing personally the true God through His Son, Jesus Christ. To know Him is life (John 17:3), and to know Him is to trust Him. For He is love and love begets trust. The death of Christ for us not only demonstrates God’s love for us but is also the means by which that love is made known to us. By Jesus entering into our death through His death on the cross, God could remove that death in the resurrection of Jesus. Now in the resurrection of Jesus the barrier of death is removed. We see God revealed as never before. We know Him now, having been made alive to God in the resurrection of Jesus. To be alive spiritually is to know God (John 17:3). And being made alive to God in Jesus is to know the love of God. Thus the death of Jesus is more than a demonstration of love — it is the means by which that love could remove the barrier of death, and thus make us alive to God Himself, revealing Himself to us. The trust that this love invokes is righteousness; it relates us rightly to God. Thus by taking away death, God takes away sin. And by taking away sin, God takes away His wrath — no sin, no wrath.

Being made alive, we are set right with God through faith. We are justified — set right — through the faith that resulted from the righteousness of God; that is, the act of God by which He sets us right with Himself. God sets us right with Himself by making us alive to Himself. And the faith flowing from that life is that right relationship to Him. It is faith in the risen Christ through Whom we are made alive to God that is righteousness (Rom. 10:9-10). Justification is not a legal act but the real act of God whereby He puts us into a right personal relationship — sets us right — with Himself. He did this by making us alive to God in Christ. This is no legal fiction but reality — we are alive to God in Christ. And being made alive, we believe; we trust the God we now know, having been made alive to Him. This faith is righteousness; it relates us rightly to God (it is the opposite of the sin of idolatry – trust in a false god). This righteousness of faith is no legal fiction. To be alive to God is to trust Him. And this is the reality that the salvation of God has produced. God is not concerned about legal formalities and technicalities. He is concerned about the reality of making us alive to Himself, and the faith that trusts Him and His love.

The Biblical concept of the righteousness of God is the act or activity of God whereby He puts or sets right that which is wrong. Very often in the Old Testament it is the action of God for the vindication and deliverance of His people; it is the activity in which God saves His people by rescuing them from their oppressors.

“In thee, O Lord, do I seek refuge; let me never be put to shame; in thy righteousness deliver me!” (Psa. 31:1)

“In thy righteousness deliver me and rescue me; incline thy ear to me, and save me!” (Psa. 71:2)

“11 For thy name’s sake, O Lord, preserve my life! In thy righteousness bring me out of trouble! 12 And in thy steadfast love cut off my enemies. and destroy all my adversaries, for I am thy servant.” (Psa. 143:11-12)

Thus the righteousness of God is often a synonym for the salvation or the deliverance of God. In the Old Testament, this is clearly shown by the literary device of parallelism which is a characteristic of Hebrew poetry. Parallelism is that Hebrew literary device in which the thought and idea in one clause is repeated and amplified in a second and following clause. This parallelism of Hebrew poetry clearly shows that Hebrew poets and prophets made the righteousness of God synonymous with divine salvation:

“The Lord hath made known His salvation: His righteousness hath he openly showed in the sight of the heathen.” (Psa. 98:2 KJV)

“I bring near my righteousness, it shall not be far off, and my salvation shall not tarry; and I will place salvation in Zion for Israel my glory.” (Isa. 46:13 KJV)

“My righteousness is near, my salvation is gone forth, and mine arms shall judge the people; the isles shall wait upon me, and on mine arm shall they trust.” (Isa. 51:5 KJV)

“Thus saith the Lord, keep ye judgment and do justice [righteousness]: for my salvation is near to come, and my righteousness to be revealed.” (Isa. 56:1 KJV; See also Psa. 71:1-2, 15; 119:123; Isa. 45:8; 61:10; 62:1)

From these verses it is clear that righteousness of God is a synonym for the salvation or deliverance of God. The righteous acts of the Lord, or more literally, the righteousnesses of the Lord, referred to in Judges 5:11; I Sam. 12:7-11; Micah 6:3-5; Psa. 103:6-8; Dan. 9:15-16, means the acts of vindication or deliverance which the Lord has done for His people, giving them victory over their enemies. It is in this sense that God is called “a righteous God and a Savior” (Isa. 45:21 RSV, NAS, NIV) and “the Lord our righteousness” (Jer. 23:5-6; 33:15-16).

A judge or ruler is “righteous” in the Hebrew meaning of the word not because he observes and upholds an abstract standard of Justice, but rather because he comes to the assistance of the injured person and vindicates him. For example, in Psalm 82:2-4 (NAS), God says to the rulers:

2How long will you judge unjustly, And show partiality to the wicked? 3Vindicate the weak and fatherless; Do justice [judgment] to the afflicted and destitute. 4Rescue the weak and needy; Deliver them out of the hand of the wicked.” (Psalm 82:2-4 [NAS].

See also Psa. 72:4; 76:9; 103:6; 146:7; Isa. 1:17.)

For the judge to act this way is to show righteousness. (See Psa. 72:1-4.) The righteousness of God is not opposed to the love of God nor does it condition the love of God. On the contrary, it is a part of and the proper expression of God’s love. It is the activity of God’s love to set right the wrong. In the Old Testament, this is shown by the parallelism between love and righteousness.

“But the steadfast love of the Lord is from everlasting to everlasting upon those who fear him, and his righteousness to children’s children.” (Psa. 103:17 RSV; see also Psa. 33:5; 36:5-6; 40:10; 89:14.)

God expresses His love as righteousness in the activity by which He saves His people from their sins. In His wrath, God opposes the sin that would destroy man whom He loves. In His grace, He removes the sin. The grace of God is the love of God in action to bring salvation.

“4 But God, who is rich in mercy, out of the great love with which He loved us, 5 even when we were dead in our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ (by grace you have been saved).” (Eph. 2:4-5)

“For the grace of God that brings salvation has appeared to all men.” (Titus 2:11 NIV).

Thus the righteousness of God may be considered as the proper expression of the grace of God. For in His righteousness God acts to deliver His people from their sins, setting them right with Himself. There is a difference between the righteousness of God in the Old Testament and that in the New Testament. In the Old Testament, the righteousness of God is the vindication of the righteous who are suffering wrong (Ex. 23:7). God vindicates the righteous who are wrongfully oppressed. In the Old Testament, the righteousness of God requires a real righteousness of the people on whose part it is done. In Isa. 51:7, the promise of deliverance is addressed to those “who know righteousness, the people in whose hearts is my law.” Similarly, in order to share in the promised vindication, the wicked must forsake his ways and the unrighteous man his thoughts, and return unto the Lord (Isa. 55:7). In the New Testament, the righteousness of God is not only a vindication of a righteous people who are being wrongfully oppressed (this view is in Jesus’ teaching in Matt. 5:6; 6:33; Luke 18:7), but it is also a deliverance of the people from their own sins; it is also the salvation of the ungodly who are delivered from their ungodliness (trust in a false god) and unrighteousness. The righteousness of God saves the unrighteous by setting them right with God Himself through faith. This righteousness of God has been manifested, that is, publicly displayed, in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

“21 But now apart from the Law the righteousness of God has been manifested, being witnessed by the Law and the Prophets;

22 even the righteousness of God through faith in Jesus Christ for all those who believe; for there is no distinction;”

(Rom. 3:21-22 NAS).

The righteousness of God, as we have just seen, is God acting in love to set man right with God Himself and is synonymous with salvation. Now this righteousness of God has been manifested (phaneroo), that is, publicly displayed, in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. God was active in the death and resurrection of Christ for man’s salvation. And because He is this act of God for man’s salvation, Jesus Christ is the righteousness of God (I Cor. 1:30). And since the gospel or good news is about Jesus Christ, who He is and what He did (Rom. 1:3-4; I Cor. 15:3-4), it is about this manifestation of the righteousness of God. The gospel tells us about God’s act of salvation in the person and work of Jesus Christ; the gospel is the gospel of our salvation (Eph. 1:13).

But the gospel is not only about the righteousness of God manifested in the past on our behalf, but in the preaching of the gospel the righteousness of God is being continually revealed (apokalupto) in the present.

“For in it [the gospel] the righteousness of God is being revealed from faith unto faith” (Rom. 1:17a ERS).

The revelation that is spoken of in this verse is not just a disclosure of truth to be understood by the mind, but it is a working that makes effective and actual that which is revealed. Hence, the revelation of the righteousness of God is that working of God that makes effective and actual that which is revealed, that is, the righteousness of God. When the gospel is preached, God is acting to set man right with Himself. The result of God’s activity of righteousness is the righteousness of faith (Rom. 4:13), the righteousness from God (Phil. 3:9), since it has been received from God by faith.

The revelation of the righteousness of God (Rom. 1:17) is also called justification (Rom. 3:24). As we have just seen, the righteousness of God is the act or activity of God whereby God sets man right with God Himself. Hence the revelation of the righteousness of God is this act of setting right, and this act of setting right is called justification. Justification is not just a pronouncement about something but is an act that brings about something; it is not just a declaration that a man is righteous before God but it is a setting of a man right with God: a bringing him into a right relationship with God. Justification is then essentially salvation: to justify is to save (Isa. 45:25; 53:11; see Rom. 6:7 where dikaioo is translated “freed” in RSV). This close relationship between these two concepts is more obvious in the Greek because the Greek words translated “justification” and “righteousness” have the same roots, not two different roots as do the two English words.

This Biblical concept of the righteousness of God must be carefully distinguished from the Greek-Roman concept of justice. The righteousness of God in the Scriptures is not an attribute of God whereby He must render to each what he has merited nor a quantity of merit which God gives, but God acting to set man right with God Himself. Luther’s apparent identification of the righteousness of God with the righteousness from God lead eventually to the equating of the righteousness from God with Christ’s righteousness, that is, the merits of Christ, which Christ earned by His active obedience before He died on the cross and is imputed to the believer’s account. Righteousness is misunderstood as merits and the righteousness of God as the justice of God. The idea that the righteousness of God is the justice of God, that is, that attribute of God which requires that God punish all sin and reward all meritorious works, is a legalistic misunderstanding of the Biblical concept of the righteousness of God. This legalistic misunderstanding reduces and equates the righteousness of God to justice, that is, the giving to each that which is his due to them with a strict and impartial regard to merit (as in Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics). It is this concept of righteousness that gave Luther so much trouble.

It is at this point that the Biblical doctrine of salvation opposes that misunderstanding and distortion of the law called legalism. In chapter 3, we discussed the law of God as God’s covenant with Israel and legalism as a misunderstanding and distortion of that law. Theologically, legalism is a distortion of the law of God, a misunderstanding of the law that was given by God to Israel. The law of God is not legalism. The law of God was a covenant relationship between God and the people Israel. Unlike the covenants God made with Noah and with Abraham, which were covenants of sheer grace, with no conditions attached to the receiving of the blessings of the covenant, the Mosaic covenant was conditional. God made unconditional promises to Noah and to Abraham of what God Himself would do. But the blessings of the Mosaic covenant were conditioned upon Israel’s obedience to God (Deut. 28:1-14); their disobedience to Him would bring curses upon them (Deut. 28:15-20; 30:1-20). These conditions are given in the Ten Commandments (Ex. 20:3-17; Deut. 5:6-21) and other statutes and ordinances. These commandments were not an end in themselves; they were specific ways in which they were to obey God. The law is concerned with Israel’s personal relationship to God: to love and obey God and not to worship or serve other gods. The history of Israel shows that they did not obey God. They disobeyed Him by turning from Him to other gods. From the time of Moses through the times of the judges and kings they kept backsliding into idolatry. The prophets over and over again rebuked them for the sin of idolatry. The curses that God said He would bring upon them for their disobedience and idolatry (Deut. 28:36-52, 63-66; 29:24-28) came upon them; they were scattered among the nations: the northern tribes in 722 B.C. by Assyria and the southern tribes in 586 B.C. by Babylonia. When they returned from the 70 years of Babylonian captivity, the Jews never again went into the idolatry of worshipping pagan gods. But it seems that very soon after the last of the O.T. prophets, Malachi, they developed an idolatry of the law. They began to trust in the law (Rom. 2:17). The law became an absolute standard to be obeyed. Obedience to the law subtly took the place of obedience to God. Keeping the law became a meritorious work that could earn God’s favor and blessings. Eventually there evolved the idea that one’s eternal destiny depends upon the amount of merit or demerit that one accumulates during one’s life-time. This whole scheme of merit with its absolute standard of the law is what we mean by legalism.

Jesus and the early apostles, particularly Paul, opposed this Jewish legalism. Paul combated the Judaizers’ attempts to put Christians under the Mosaic law. When we realize the covenant nature of the law, we can see why this was not possible. Since the Christian’s relationship to God was already established in the New covenant, it could not at the same time be established under the Old Mosaic covenant. Then it must be that what the Judaizers were trying to do was to make the law in an absolute sense necessary for a right relationship to God. This is not just the Mosaic law; it is legalism. And Paul refused to allow it. In Eph. 2:8-9, Paul contrasts salvation by grace with salvation by works.

“8 For by grace you have been saved through faith; and that not of yourselves, it is the gift of God, 9 not as a result of works, that no one should boast.” (Eph. 2:8-9 NAS)

What is salvation by works? Salvation by works is a salvation that is earned; it is merited.

“4 Now to the one who works his wages is not reckoned according to grace [as a gift] but according to debt [something owed since it was earned] 5 But to the one who does not work, but believes in Him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is reckoned for righteousness.” (Rom. 4:4-5 ERS).

The works that are supposed to earn salvation are more than just good works (good deeds or acts); they are meritorious works; they are good deeds that earn salvation. Each good work is regarded as having a certain quantity of merit attached to it; when the good work is done, the merit is placed or reckoned to the account of the person performing the act. Correspondingly, each evil or bad work is regarded as having a certain quantity of demerit or negative merit (penalty) attached to it so that the demerit is reckoned to the account of the person doing the evil work (sin). At the final judgment, each person’s account is balanced – the merits and demerits are weighed against each other. If the merit outweighs the demerit, that person is saved – he has earned eternal life. If the demerit outweighs the merit, that person is condemned – he is punished eternally for his sins. This merit scheme underlies and is implied by all teaching that salvation is by works.

Paul very clearly teaches that salvation is not by works ( Eph. 2:8-9; Titus 3:5). Salvation is by grace through faith. Salvation is a gift received by faith. Man cannot be saved by his meritorious good works; he cannot earn salvation by his works. This is the clear and explicit teaching of Scripture. Salvation by grace and salvation by meritorious works are mutually exclusive and opposing ways of salvation.

“But if it is by grace, it is no longer by works; otherwise grace would no longer be grace.” (Rom. 11:6)

Even though Paul’s opposition to the Judaizers in the early church effectively stopped the entrance into Christianty of the Jewish legalism (see the Letter to the Galatians), this did not stop another form of the legalism from creeping into Christian thought and practice some 200 years later. In this later form of legalism, the rationalism of the Greek philosophers had been wedded to the legal philosophy of the Romans developed by such earlier writers as Cicero (1st century B.C.). This rationalistic legalism crept into Christian theology by way of a 3rd century lawyer and Christian apologist, Tertullian, and since the time of Augustine (5th century) has formed the basis of most Roman Catholic and Protestant theology.

Legalism — as basically an idolatry of the law — leads to and involves a misunderstanding of sin and death. Legalism misunderstands sin as only law breaking, as falling short of the universal standard of the law. And death is misunderstood as always the penalty of sin. And the wrath of God is misunderstood as only the punishment of sin. The immediate personal origin of sin has been misunderstood to be an inherited sinful nature, making sin instrinsic to human nature and implying a denial of human freedom and responsibility. This legalistic conception of sin and death leads to a misunderstanding of the need for salvation and the nature of salvation.

In chapter 4, we discussed this legalistic misunderstanding of the need for salvation. According to this legalistic view, man needs salvation because he is a guilty sinner. He is guilty not only because of his own personal sins, transgressions of the law, but because of the sin of Adam whose sinful nature he has inherited. This legalistic misunderstanding of the need of salvation came into Christian theology through Tertullian (3rd century) and Cyprian (4th century) and was fixed upon Christian theology by Augustine in the early fifth century A.D. This came about in connection with his controversy with a British monk, Pelagius. The legalistic misunderstanding of the need for salvation underlies this controversy. Both Augustine and Pelagius assumed that eternal life was something that had to be earned by meritorious works; it was a reward for righteousness or meritorious good works. But they differed on whether man was able or free to do such good works. Pelagius taught that by grace of nature, man was free not to sin and to do good works. But Augustine taught that the grace of nature was lost by the fall and man was not free not to sin and to do good works; only by the special grace of God in Jesus Christ is man able not to sin and to do good works. Apart from this difference concerning nature and grace (and the doctrine of original sin), Augustine and Pelagius both assumed that eternal life was basically a meritorious reward, and freedom to do good works was given by God’s grace in order that man might receive eternal life as a reward for his meritorious good works that grace made possible. This conception of salvation of both of them is basically legalistic: eternal life is something that has to be earned by meritorious good works. But because the grace of God makes good works possible, salvation is also by grace.

The difference between Augustine and Pelagius centered in the doctrine of original sin. Augustine appealed to the doctrine of original sin to support his denial of human freedom not to sin. The whole race, Augustine held, was corrupted in the first or original sin of Adam and from Adam each member of the human race received a sinful nature. This nature expresses itself in sinful acts. Because of his sinful nature, man is not able not to sin (non posse non peccare); he has lost his freedom not to sin and to do good works. Because all men literally sinned in Adam, their natural head, they are all guilty and have all inherited the guilt of that sin. Men are under condemnation not only because of their own personal sins, which each commits as an expression of his sinful nature, but because of the guilt of the original sin in which they participated in Adam before they were born. Thus man cannot save himself. He is not able not to sin and also not able to do the meritorious works that could earn him eternal life. This reasoning assumes that salvation is by works but man is not able to do the works.

After the Reformation, many Protestant theologians reinterpreted the doctrine of original sin. During the seventeenth century, it became known as covenant or federal theology. Among its earliest advocates were the Swiss reformer Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531) and his successor, Johann Heinrich Bullinger (1504-1575), who were driven to the subject by the Anabaptists in and around Zurich. From them it passed to John Calvin (1509-1564) and to other Reformers; it was further developed by their successors, and played a dominant role in Reformed theology of the seventeenth century. Its emphasis on God’s covenantal relationships with mankind was seen as less harsh than the earlier Reformed theology that emanated from Geneva, with its emphasis on divine sovereignty and predistination. From Switzerland the covenant theology passed over into Germany. The German linguist and theologian Johann Koch [latinized to Cocceius] (1603-1669) set forth in his Doctrine of the Covenant and Testaments of God (1648) and in his Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans (1655) the fully developed covenant theology. It spread from there to the Netherlands and to the British Isles where it was incorporated into the Westminster Confession of Faith (1648); it came to have an important place in the theology of Scotland and of New England.

Whether man has had the guilt of Adam’s sin imputed to him or he is guilty because he somehow sinned in Adam, man is guilty. Upon him rests the load of racial guilt as well as the guilt from his own personal sins. He needs to be saved because he is guilty. Salvation is accordingly conceived of as a removal of that guilt. In chapter 5, we discussed this legalistic misundertanding of salvation. According to the legalistic theology, justice requires that the penalty be paid before the guilt can be removed. It cannot be forgiven freely but can be only taken away by paying of the penalty which alone can satisfy justice. Because of the enormity of the guilt — it is against an infinite moral being — finite man himself can never pay the penalty and go free. His sin demands an eternal punishment, and being finite man cannot meet the infinite demands of justice. If man is to be saved at all, he must be saved by another, by one who is a man like himself but without sin. But also one who is God who alone can meet the infinite demands of justice. Where is such a one to be found? Only God can provide that one, and God has provided the perfect sacrifice to pay the penalty of sin by sending His Son to become man. His death is the perfect sacrifice to satisfy the demands of justice. It can remove the guilt by paying the penalty of sin. In His death, He endured the eternal punishment due to man’s sin.

According to this legalistic theology, it is not enough just to be declared not guilty, man must be also have a righteousness which merits eternal life. He must not only have no guilt, no demerits, but he must also have a positive righteousness, merits placed to his account. Since man cannot earn this righteousness himself because of his sinful nature (he is not able not to sin and not able to do righteousness — good works which merit eternal life as a reward), someone must earn this for him. According to this legalistic point of view, salvation is not only a vicarious satisfation of the demands of justice and the law, but it is also vicarious law-keeping. Christ’s life of active obedience under the law provides that righteousness — Christ has earned for us eternal life by His active obedience before His death on the cross. By His passive obedience of His death on the cross, He paid the penalty of our sins. Therefore, the one who receives in faith Christ’s work for him is declared not guilty, and Christ’s righteousness or merits of Christ is imputed to his account. The believer is justified, declared righteous, because Christ has satisfied the demands of justice and fullfilled the law for us. The believer is legally entitled to eternal life if he receives it from Christ who earned it for him. Thus salvation is understood legalistically. It is a legal transaction — a fire insurance policy that another paid for and given freely to anyone if they will take it.

This is a consistent and logical explanation of salvation and man’s need of salvation. There is only one difficulty with it — it is not true. Yes, Christ died for man to take away his sin. The fact of Christ — who He is and what He did — is true, but the explanation is all wrong; it is legalistic. Salvation is not by works, even though another — even God — performs them. God is not the kind of God that the legalist thinks He is. He is not a God of justice but a God of love. The righteousness of God has been misunderstood as justice. According to the Scriptures (Psa. 31:1; 71:2; 143:1-2; 98:2; Isa. 46:13; 51:5; 56:1), the righteousness of God is the act of the love of God by which God sets us right with Himself and saves us. God sets us right with Himself by making us alive to Himself. And the faith flowing from that life is that right relationship to Him. It is faith in the risen Christ through Whom we are made alive to God that is righteousness (Rom. 10:9-10). Justification is not a legal act but is the real act of God whereby He puts us into a right relationship — sets us right — with Himself. He did this by making us alive to God in Christ (Rom. 4:25; 5:18). This is no legal fiction but a reality — we are alive to God in Christ.

In chapter 6, we discussed the effect of this legalism on the problem of the atonement — why “must” Christ die for the salvation of men? This problem of the necessity of the atonement is the major problem of the Christian doctrine of salvation. In chapter 6, we examined this central problem of Christian theology. We examined first the classic type of the atonement and then we clarified the difference between the classic type and the Latin type. In conclusion, we summarized the characteristics of the classic type:

1. The classic type is dramatic.

Christ’s death and resurrection is a divine conflict and victory. Christ in his death and resurrection fights against and triumphs over the evil powers of the world, primarily death, and thus reconciles the world to Himself.

2. The classic type is dualistic.

This is not a metaphysical or absolute dualism but a relative dualism between death and life. It is a conflict between God and the powers of evil who have rebelled against His authority and who are defeated in Christ’s death and resurrection. Satan who has the power of death (Heb. 2:14) has been destroyed through Christ’s death and resurrection.

3. The classic type is cosmic.

The problem that was solved by Christ’s death and resurrection is in man and in the world and not in God. The evil powers that Christ fights against and triumphs over are in the world.

4. The classic type is single-sided.

God is the Reconciler, not the Reconciled.

Reconciliation is salvation from death to life. Since the problem is not in God, God does not need to be reconciled.

5. The classic type is non-legalistic.

The classic type makes no legalistic assumptions about the need for salvation or the nature of salvation. There is not only no discontinuity in the order of merit and justice but there is complete absence of the order of merit and justice in the classic type.

And then we showed how in the Latin type the meaning of the death of Christ has been misunderstood and was obscured by the Greek-Roman concept of justice: giving to each what he has merited. This concept of justice, which has misunderstood and obscured the righteousness of God and the love of God, has lead to the legalistic misunderstanding of the death of Christ.

Finally, in chapter 6, the Biblical doctrine of Christ’s death was presented and how it solves the problem of the necessity of the atonement. The Biblical and classic solution to the problem of the necessity of the atonement is that Christ must die if man is to be saved. The problem that the atonement solved is not in God but in man: it is man who is dead and sins because he is dead ( Rom. 5:12d ERS). Thus Christ died primarily to save man from death and secondarily to save him from sin and hence from wrath. The necessity of the atonement is not in God and hence absolute, but in man and hence relative. It is not the justice of God that requires the death of Christ but the love of God who wants to save man. It is not God’s justice that is the barrier to man’s salvation but it is death. And Christ’s death and resurrection has overcome that barrier. Death is a real and objective barrier to man’s salvation; death separates man from God (spiritual death) and man’s spirit from his body (physical death). Death had to be defeated and this is not just dramatic and emotional language. Neither the objective or subjective theories of the atonement understands nor takes seriously this problem. Since death came by a man, Adam, so death had to be removed by a man, the God-man, Jesus Christ (I Cor. 15:21-22). All legalistic theories of the atonement see sin as the primary problem; death is always a secondary problem because death is always seen as the necessary penalty of sin. They assume that the law can make alive, contrary to the clear statement of the Scriptures.

Paul says in his letter to the Galations:

“Is the law against the promises of God? Certainly not; for if a law had been given which could make alive, then righteousness would be indeed by the law.” (Gal. 3:21)

If the law could make alive, then the death and resurrection of Christ would be unnecessary and Christ died in vain (Gal. 2:21). But the law cannot make alive; therefore, salvation is not by the law. Thus any legalistic interpretation of the atonement cannot be true because the law cannot make alive and can not produce righteousness; it cannot save from death and sin.

The Biblical and classic solution sees death as the primary problem and sin as a secondary problem because man sins because of death ( Rom. 5:12d ERS). The death and resurrection of Christ solves the problem of death by making us alive to God in and with the resurrection of Christ. It thus solves the problem of sin. God saves us from sin itself (primarily, idolatry – trust in a false god) to the righteousness of faith (trust in the true God) by making us alive to God, when we receive by faith the gift of eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.

The problem solved by Christ’s death was not in God but in man. God did not have to be reconciled and His justice satisfied before man could be saved. On the contrary, it is man who needs to be reconciled to God; it is man who needs to be changed. Man is dead and he needs to be made alive. The problem is in man — he is dead and he needs life. Man does not need a lawyer; he needs someone to raise him from the dead. And only God can do that, and He has done it through His Son’s death and resurrection. God was in Christ reconciling the world unto Himself (II Cor. 5:19) — not reconciling God to the world. And God in reconciling us to Himself through Christ has made us alive to Himself by His resurrected life (Rom. 5:10). And since man sins because he is dead ( Rom. 5:12d ERS), by making him alive, God saves him from sin to righteousness. He saves him not just from the guilt of sin but from sin itself. And He saves him not from just breaking the law but from trusting in a false god. God saves man to trust in God Himself — the only real righteousness, the righteousness of faith (Rom. 4:5, 13). Legal righteousness (merits) is not enough. For the real law wants faith, trust in and love of God — “and you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul and with all your might.” (Deut. 6:5)

And since death is the barrier that hinders this, God has removed this barrier and hindrance by the death and resurrection of His Son. He entered into our death so that we could enter into His life — by being made alive to God with Christ through His resurrection. And being made alive with Him, we can now trust, love, and worship Him. This is true righteousness. So then, just as sin flows out of death, so righteousness flows out of life — out of Jesus Christ who is the Life. Life is not some thing; it is a person — Jesus Christ — and to have Him and know Him and the true God through Him is to have Life (John 17:3; I John 5:11-12). And to know Him and His love is to trust Him. Love begets trust. And to walk in this love by faith is the Christian life.

In chapter 7, we discussed the effect of this legalism on the Christian life. Legalism makes a problem of the Christian life, because it puts the Christian under law, separating him from God. It leads him to trust in the law and in himself and in his works (trust in the flesh) rather than in the Spirit of God. The result is defeat and dispair of the man under law as described in Romans 7. Chapter 7 of Romans is not the normal Christian life, but a abnormal or subnormal Christian life, under law. This is the practical effect of the legalistic theory of Christ’s death — by putting the Christian under law, the Christian becomes a slave of sin. Sin uses the law as an occasion to become active (Rom. 7:8, 11). Legalism does not work. Where is the victory of Christ’s resurrection in the struggle of Romans 7? Only as we are delivered from being under the law — we died to the law in Christ’s death (Rom. 7:4) — and as we are set free from law of sin and of death by the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus (Rom. 8:2), do we experience the resurrection victory of Christ over sin and death. The Christian life is not Spirit-empowered law-keeping, but Spirit-filled law-fulfilling by love (Rom. 8:4; 13:10); it is a joyful walk being filled with the Spirit, trusting Him who loved us and gave Himself for us.

And if we trust and love God, is any law necessary to make us to do so? The law is for them who do not love and trust God — though it will not save them — it cannot make them alive; it cannot produce righteousness ( Gal. 3:21). For if the law could make them alive, as legalism tries to tell us, then Christ died in vain (Gal. 2:21). Salvation is not by the works of the law — in any way, shape or form. Salvation is by the grace of God — God’s love in action to make us alive to God in Christ through faith, through trust in Him Who loves us and gave Himself for us (Eph. 2:4-6). The Christian life begins by grace through faith; this is the past tense of salvation.

“For by grace you have been saved through faith” (Eph. 2:8).

The Christian life, which is the present tense of salvation, is also by grace through faith. “As you therefore have received Christ Jesus the Lord, so walk in Him” (Col. 2:6 NAS). Because God so loved us, He has acted in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ for the salvation of man from death, sin and wrath. Since wrath is caused by sin (Rom. 1:18) and sin by death ( Rom. 5:12d ERS), salvation is basically from death to life and then from sin to righteousness and then from wrath to peace with God. God contemporaneously and personally is accomplishing this salvation through the Holy Spirit. After raising Jesus from the dead and exalting Him to His own right hand to be both Lord and Christ (Acts 2:33, 36; Eph. 1:20-22; Phil. 2:9-11), God sent the Holy Spirit (Acts 2:33) to give life to men (John 3:5-8) by revealing Jesus to them (John 15:26) personally as their Savior who died for them and as their resurrected, living Lord. This revelation takes place in the preaching of the Gospel of God concerning Jesus Christ, His Son. And when one responds to this revelation by turning from his false gods (repentance) and turning to the true God, acknowledging Jesus as his Lord (faith), he is saved (Acts 16:31).

CONCLUSION

In this act of faith, man is delivered from death, sin and wrath to life, righteousness and peace with God. But this is only the beginning. There are three tenses of salvation:

1. the past tense — we have been saved,

2. the present tense — we are being saved,

3. and the future tense — we shall be saved.

In the past tense of salvation at conversion, we have been saved from death unto life, from sin unto righteousness, and from wrath unto peace. But this salvation is not yet complete. It has begun for those who are in Christ Jesus (Rom. 8:24), and it is still continuing (I Cor. 15:2; see also I Cor. 1:18 and II Cor. 2:15). In the present tense of salvation, now we are being transformed into and conformed to the image of God (Rom. 8:29; II Cor. 3:18). The resurrected God-man, the Son of man, Jesus Christ, is the image of God (Col. 1:15; II Cor. 4:4). By the last Adam, the man from heaven, man is being restored to the image of God. In faith, we have put on the new man which is being renewed according to the image of Him who created him (Col. 3:10; Eph. 4:23-24). This is the present tense of salvation.

But there is still a future tense of salvation: we shall be saved when Christ returns to reign (Rom. 8:23). When He returns, we will bear the image of the man of heaven — Christ (I Cor. 15:47-49). For “when he shall appear, we shall be like Him; for we shall see Him as He is” (I John 3:2). At the second coming of Jesus Christ (Acts 1:9), our bodies will be resurrected if we die before He comes (I Thess. 4:14-17), or they will be transformed into ones like His resurrected body if we are alive at His coming (I Cor. 15:51-52; Phil. 3:20-21; I John 3:2). Thus will physical death be replaced with physical life as spiritual death was replaced with spiritual life when we first repented and believed (conversion). What was begun at conversion will be brought to completion (Phil. 1:6) at Christ’s coming, the day of Jesus Christ. Spiritual life will become eternal life — eternal fellowship with the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit (Rev. 21:3). We shall reign with Him (II Tim. 2:12; Rev. 20:4) and will be with Him (I Thess. 4:17; Rev. 22:4) forever. We shall be His people, and He shall be our God (Rev. 21:3, 7). Thus will man be comletely restored to the image of God. And our salvation from death (both spiritual and physical) unto life, from sin (idolatry — trust in false gods) unto righteousness (trust in the true God), and from wrath to peace with God will be completed. Praise God!

EPILOGUE

Martin Luther recovered the Biblical concept of the righteousness of God and of the justification by faith. But his followers obscured this understanding of these concepts by the legalism of their theology and legalistic understanding of righteousness and justification. And this legalism not only affected their theology but the whole life of the church. The result of this legalism was dead orthodoxy and a cold, unloving Christianity. To correct these effects there arose in the church various movements such as pietism, the evangelical awakening, revivalism, etc. None of these movements went to the source of the deadness, coldness and unlovableness but just reinforced the cause — legalism.

The great outpouring of the Spirit starting at the beginning of the twentieth century has been hindered and limited by the constant relapses into the same legalism. And the source of this legalism in practice is the legalism of the theology. The theological legalism produces the practical legalism. The answer to the legalism of the theology is not no theology, but a non-legalistic theology, a Biblical theology. With the present move of the Spirit, the time has come to clear the legalism out of our theology and again recover the Biblical understanding of the righteousness of God and justification by faith. The examination of the Biblical doctrine of salvation and the need for salvation in my book, From Death to Life, is an attempt to make a beginning of this theological renewal.