rog2

RIGHTEOUSNESS OF GOD

As we have seen, the righteousness of God is the act or activity of God whereby God sets man right with God Himself. Hence the revelation of the righteousness of God is this act of setting right, and this act of setting right is called justification. Justification is not just a pronouncement about something but is an act that brings about something; it is not just a declaration that a man is righteous before God but is a setting of a man right with God: a bringing him into a right relationship with God. Justification is then essentially salvation: to justify is to save (Isa. 45:25; 53:11; see Rom. 6:7 where dikaioo is translated “freed” in RSV). This close relationship between these two concepts is more obvious in the Greek because the words translated “justification” and “righteousness” have the same roots, not two different roots as do the two English words. See my Word Study on “righteousness”.

In the New Testament, justification is not just a vindication of the righteous who has been wronged (this view is in Jesus’ teaching in Matt. 5:6; 6:33; Luke 18:7), but it is also the salvation of the ungodly who are delivered from their ungodliness and unrighteousness;

“And to the one who does not work but trusts him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is reckoned as righteousness” (Rom. 4:5).

Justification not only saves the ungodly from their sins, it also brings them into the righteousness of faith. Justification is not a legal declaration or pronoucement of one’s legal status (the Protestant doctrine of justification) nor the infusion of His grace in order that one may earn salvation (the Roman Catholic doctrine of justification); it is the activity of God for salvation. Justification is essentially salvation; to justify is to save (Isa. 45:25; 53:11). The righteousness of God is not justice nor is it the righteousness from God; these are different though related concepts. The righteousness from God is the righteousness of faith; it is being set right with God by man’s response of faith to the righteousness of God, God’s activity of setting him right with Himself. To be set right with God is to have faith in God. And this faith in God is reckoned for righteousness, the righteousness of faith.

“Abraham believed God, and it [his faith] was reckoned unto him for righteousness.” (Gen. 15:6).

“4:3 For what does the scripture say? ‘Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness.’ 4:4Now to one who works, his wages are not reckoned as a gift but as his due. 4:5And to the one who does not work but trusts him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is reckoned as righteousness …. 4:13The promise to Abraham and his descendants, that they should inherit the world, did not come through the law but through the righteousness of faith.” (Rom. 4:3-5, 13).

(See also Rom. 4:9b; Rom. 10:9; Phil. 3:9).

Justification, as God’s act of setting man right with God Himself, brings man into faith, in which man is set right with God, that faith being reckoned as righteousness, the righteousness of faith. And justification ( Rom. 3:24) is also the revelation of the righteousness of God (Rom. 1:17). Since the righteousness of God is the act or activity of God whereby God sets man right with God Himself, then this act of setting right is the actualization or revelation of the righteousness of God, and this act of revelation of the righteousness of God (Rom. 1:17) is also called justification ( Rom. 3:24).

There is a difference between justification in the Old Testament and that in the New Testament. In the Old Testament justification is the vindication of the righteous who are suffering wrong (Ex. 23:7). God justifies, that is, vindicates the righteous who are wrongfully oppressed. Justification requires a real righteousness of the people on whose part it is done. In Isa. 51:7 the promise of deliverance is addressed to those “who know righteousness, the people in whose hearts is my law.” Similarly, in order to share in the promised vindication, the wicked must forsake his ways and the unrighteous man his thoughts, and return unto the Lord (Isa. 55:7). However, in the New Testament justification is not only a vindication of a righteous people who are being wrongfully oppressed but also a deliverance of the people from their own sins. Thus, Paul says that God is He “that justifies the ungodly” (Rom. 4:5). In the New Testament, justification is not just a vindication of the righteous who has been wronged (this view is in Jesus’ teaching in Matt. 5:6; 6:33; Luke 18:7), but also the salvation of the ungodly who is delivered from his ungodliness and unrighteousness. But justification not only saves the ungodly from their sins, it also brings them into the righteousness of faith. To be set right with God is to have faith in God.

“Abraham believed God, and it [his faith] was reckoned unto him for righteousness” (Gen. 15:6; Rom. 4:3,9; cf. Rom. 10:9; Phil. 3:9).

Justification as God’s act of setting man right with Himself brings man into faith, which is to be set right with God. Thus justification is through faith (dia pisteos, Rom. 3:30; Gal. 2:16) and out of or from faith (ek pisteos, Rom. 3:26,30; Gal. 2:16; 3:8, 24).

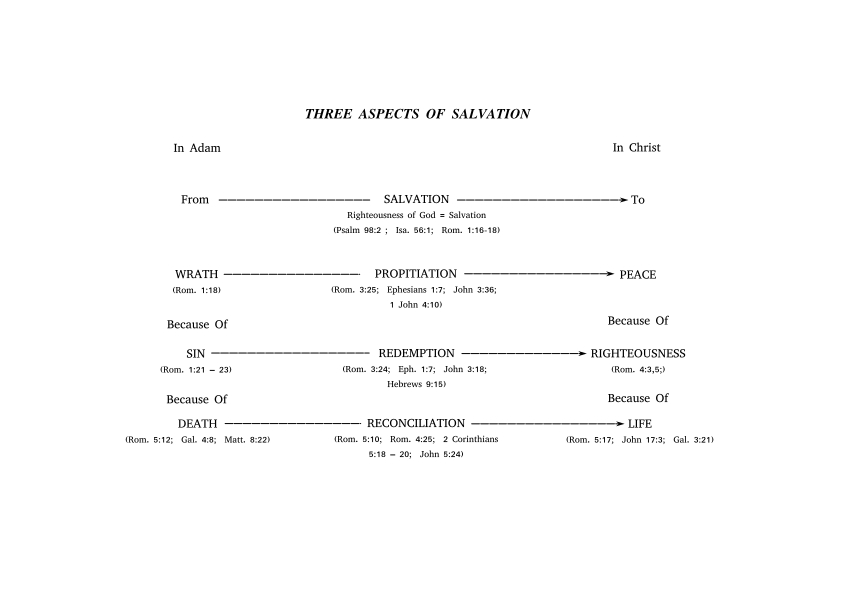

But justification as salvation is not only the deliverance from sin to righteousness but also the deliverance from wrath to peace and from death to life. Justification as deliverance from wrath to peace is set forth by the Apostle Paul in Romans 3:24-25:

“3:24 Being justified by His grace as a gift, through the redemption which is in Christ Jesus, 3:25 whom God set forth to be a propitiation, through faith in His blood.” (Rom. 3:24-25 ERS; see also Isa. 32:17).

Here Paul connects justification with the other two aspects of salvation, redemption and propitiation. Redemption is the deliverance from sin by the payment of a price called a ransom which is the death of Jesus Christ. And propitiation is the deliverance from the wrath by the sacrifical death of Jesus (“His blood”) which turns away or averts the wrath of God through faith in that sacrifice (“through faith in His blood”). Christ’s death as a propitiation turns away God’s wrath from the one who has faith in that sacrifice. The wrath is turned away because the sin has been taken away (“forgiveness”) by the death of Christ as a ransom, by which a man is redeemed or set free, delivered from sin. When sin has been removed there is no cause for God’s wrath. No sin, no wrath. Man is saved from wrath because he is saved from sin.

“Being justified freely by faith we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ.” (Rom. 5:1).

“Much more then, being justified by His blood, we shall be saved through Him from the wrath of God.” (Rom. 5:9).

Justification is also deliverance from death to life. Man is delivered from sin to the righteousness of faith because he is delivered from death to life. As sinners we were enemies of God, but through the death of God’s Son we have been reconciled to God and are now no longer enemies. To be reconciled to God means we have passed from death to life and we are saved in His resurrected life (Rom. 5:10; see II Cor. 5:17-21). We are delivered from death by being “made alive together with Him” in His resurrection (Eph. 2:5). He was “raised for our justification” (Rom. 4:25). Thus justification is justification of life (Rom. 5:18). To be set right with God is to enter into fellowship with God. And this right relationship to God is life. Justification puts us into right relationship to God and hence is a justification of life. Fellowship with God is established when God reveals Himself to man and man responds to that revelation in faith. Life is a relationship between God and man that results from this revelation and the faith response to it. Apart from this revelation the response of faith is not possible, and this revelation is the offer of life and the possibility of faith. But life is not actual unless man responds in faith to the revelation of God Himself. Life is received in the act of faith. Since God’s act of revelation is first, and man’s response in faith is second and depends upon God’s revelation, life results in the righteousness of faith and man is righteous because of life. Justification as the revelation of the righteousness of God brings about life and the righteousness of faith.

Justification is the free act of God’s grace ( Rom. 3:24; Titus 3:7). The source of justification is the love of God. And the love of God in action to bring man salvation is the grace of God (Titus 2:11). Hence justification is the true expression of the grace of God and the act of the love of God. Because justification is a gift (Rom. 3:24; 5:15-17), justification is free and is not something that can be earned (Rom. 4:4; 11:6). Being a free act of God’s grace, justification has nothing to do with the works of the law (Rom. 3:20, 28; 4:6; Gal. 2:16; 3:11; see also Eph. 2:2-9; Phil. 3:9; II Tim. 1:9; Titus 3:5). The whole legalistic theology is a misunderstanding of the righteousness of God and justification by faith, and is therefore unbiblical and false. The Scripture nowhere speaks of the righteousness or merits of Christ and of justification as an imputation of the merits of Christ to our account. The introduction of such a legalistic righteousness, even if it means the merits of Christ, into the discussion of the righteousness of God and of justification by faith obscures the grace of God and misunderstands the law as well as the gospel of the grace of God. In principle, the grace of God has nothing to do with legal righteousness and merits. God does not give man His grace by faith so that he can earn merits to gain eternal life nor to show that he is legally righteous before God. Jesus Christ did not satisfy in our place the demands of the law, either in precept or penalty. Christ fulfilled the law (Matt. 5:17), but not for us. Nowhere in the Scripture does it say that Christ fulfilled the law for us. Neither did he fulfill it legalistically. Not because Christ was not able to do it but because God does not in His love and grace operate on the basis of law or legal righteousness. Christ fulfilled it by love, for “love is the fulfilling of the law” (Rom. 13:8, 10).

Legalism misinterprets the righteousness of God as justice, that is, as that principle of God’s being that requires and demands the reward of good work (comformity to the Law) because of their intrinsic merit (remunerative justice) and the punishment of every transgression of the law with a proportionate punishment because of its own intrinsic demerit (retributive justice). According to this view, for God to do otherwise He would be unrighteous and unjust. Absolute justice, which according to this point of view is the eternal being of God, is said to require and demand, of necessity, the reward of meritorious good works and the punishment of sin. It was this legalistic concept of justice that gave Martin Luther so much trouble.

In the English language, the use of “justify” to translate the Greek verb dikaioo and the use of “justification” to translate the Greek verbal noun dikaiosis seems to imply that the righteousness of God is the Greek-Roman concept of justice. The English language has no verbal noun or verb of the same root as the English word “righteousness” to translate the Greek verbal noun or verb. This deficiency of the English language does not mean that the righteousness of God is the Greek-Roman concept of justice.

From this legalistic point of view, man needs to be saved because he is guilty of breaking the law. Salvation is accordingly conceived of as a removal of that guilt. Justice requires that the penalty be paid before the guilt can be removed. It cannot be forgiven freely but only can be taken away by the paying of the penalty which alone can satisfy justice. Because of the enormity of the guilt – it is against an infinite moral being – finite man himself can never pay the penalty and go free. From this legalistic point of view, man’s sin demands an eternal punishment, and being finite he cannot meet the infinite demand of justice. If he is to be saved at all, he must be saved by another – one who is man like himself but without sin, but also one who is God who alone can meet the infinite demand of justice. Where is such a one to be found? Only God can provide the one, and God has provided the perfect sacrifice to pay the penalty by sending His Son to become man. His death is the perfect sacrifice. It can remove the guilt by paying the penalty. In His death he endured the eternal punishment due to man’s sin.

But from this legalistic point of view, it is not enough just to be declared not guilty; man must also have a righteousness which merits eternal life. He must not only have no guilt, no demerits, but he must also have a positive righteousness, merits placed to his account. Since man cannot earn this righteousness (merits) himself because of his sinful nature (he is not able not to sin and not able to do righteousness – good works which merit eternal life as a reward), someone must earn this for him. According to this legalistic theology, salvation is not only a vicarious satisfaction of the demands of justice and the law, but it is also vicarious law-keeping. Christ’s life of active obedience under the law provides the righteousness (merits) we need; Christ earned for us eternal life by His active obedience to the law. And by His passive obedience of death on the cross He paid for us (vicariously) the penalty of our sins. Therefore, the one who receives in faith Christ’s work for him is declared not guilty, and Christ’s righteousness (the merits of Christ) is imputed to his account. He is justified because Christ has satisfied the demands of justice and the law against him. He is legally entitled to eternal life if he receives it from Christ who earned it for him. Thus salvation is understood legalistically. It is a legal transaction – a fire insurance policy that another paid for and gives freely to man if he will take it.

This is a consistent and logical explanation of salvation by Christ. There is only one difficulty with it – it is not true. Yes, Christ died for man to take away his sin. The fact of Christ – who He is and what He did – is true, but the explanation is wrong – it is legalistic. Salvation is not by meritorious works, even though another – even God – performs them. God is not the kind of God that the legalist thinks He is. He is not a God of law and justice but a God of love. Yes, God is just, that is, fair, but not in a legalistic sense. God is fair because he loves all men alike and therefore treats them impartially, without regard to their merit (Matt. 5:45). The problem solved by Christ’s death was not in God but in man. God did not have to be reconciled and His justice satisfied before man could be saved. On the contrary, it is man who needs to be reconciled to God; it is man who needs to be changed. Man is dead and he needs to be made alive. The problem is in man – he is dead and he needs life. Man does not need a lawyer; he needs one to raise him from dead. Only God can do that, and He has done it through His Son’s death and resurrection. God was in Christ reconciling the world unto Himself (II Cor. 5:18-19; see also Rom. 5:10-11) – not reconciling God to the world. And since man sins because he is dead, by making him alive God saves him from sin to righteousness. He saves him not just from the guilt of sin but from sin itself. And He saves him not just from breaking the law but from trusting in false gods. God saves man to trust in God Himself – the only real righteousness. Legal righteousness (merits) is not enough. For the real law wants faith, trust in and love of God – “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thine heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy might.” (Deut. 6:5 KJV). And since death is what hinders this, God removed this hindrance and barrier by the death and resurrection of His Son. He entered into our death so that we could enter into His life – through His resurrection. Being made alive with Him, we can now trust, love, and worship Him. So then as sin flows out of death, righteousness flows out of life – out of Jesus Christ who is the life. Life is not some thing; it is a person – Jesus Christ – and to know Him and God through Him is to be alive (John 17:3). And to know Him and His love is to trust Him.

Nowhere in the Scriptures does it say that Christ died to pay the penalty of man’s sin and satisfy God’s justice. Not in the three passages (Rom. 3:24-25; II Cor. 5:21; Gal. 3:13) usually cited to support this doctrine does it say explicitly that Christ paid the penalty of sin or satisfied the justice of God. In the Rom. 3:24-25 passage, propitiation is not the satisfaction of God’s justice; neither is redemption the paying the penality of sin.

“3:24 Being justified by His grace as a gift, through the redemption which is in Christ Jesus, 3:25 whom God set forth to be a propitiation, through faith in His blood ….” (Rom. 3:24-25 ERS; see also Isa. 32:17).

The redemption that is in Christ (Rom. 3:24) is deliverance from sin by the payment of a price, a ransom, which is the blood of Christ, that is, His sacrificial death. The price is not the payment of a penalty but it is the means by which the redemption from sin is accomplished.

“1:18Knowing that ye were not redeemed with corruptible things, like silver or gold, from your vain manner of life handed down from your fathers; 1:19but with the precious blood, as of a lamb without blemish and without spot, even the blood of Christ.”

(I Pet. 1:18-19 ERS; see also Heb. 9:14-15).

Redemption is deliverance from sin as a slave master by means of the death of Christ [His blood] as the price or ransom.

“In Him we have redemption through His blood, the deliverance from our offences, according the riches of His grace …” (Eph. 1:7 ERS).

“In whom we have redemption, the deliverance from sins. (Col. 1:14 ERS).

According to the English translations of Eph. 1:7 and Col. 1:14, redemption is made equivalent to forgiveness of sins.

“In Him we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of our trespasses, according the riches of his grace…” (Eph. 1:7 RSV).

“In whom we have redemption, the forgiveness of sins. (Col. 1:14 RSV).

But the basic meaning of the Greek word aphesis here translated “forgiveness” is “the sending off or away.” Hence to redeem from sins is to send them away, to deliver from sin. Jesus “was manifested in order to take away sins” (I John 3:5 ERS). He is “the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29).

Salvation is not just forgiveness. It is more than forgiveness of sins; salvation is also deliverance from death; it is the resurrection of the dead. Forgiveness of sins is not enough; man needs to be made alive to God because he is spiritually dead. And he is dead, not because of his own sins, but because of the sin of another, Adam. So the forgiveness of a man’s sins does not take away spiritual death because the spiritual death was not caused by that man’s sins. Thus forgiveness of sins does not remove spiritual death. But the removing of spiritual death does removes sins. Salvation as resurrection from the dead is also salvation from sin and thus it is also the forgiveness of sins. Thus to be made alive to God means that sins are forgiven.

This redemption from sin was accomplished by the death of Jesus Christ because His death is also the means by which we were delivered from death, the cause of sin. Since spiritual death leads to sin ( Rom. 5:12d ERS), sin reigns in the sphere of death’s reign (Rom. 5:21). And since Christ’s death is the end of the reign of death for those who died with Christ, it is also the end of the reign of sin over them. They are no longer slaves of sin, serving false gods. Sin is a slave master (Rom. 6:16-18) and this slave master is the false god in which the sinner trusts. We were all slaves of sin once, serving our false gods when we were spiritually dead, alienated and separated from the true God, not knowing Him personally. But we were set free from this slavery to sin through the death of Christ. For when Christ died for us, He died to sin (Rom. 6:10a) as a slave master. Sin no longer has dominion or lordship over Him. For he who has died is freed from sin (Rom. 6:7). That is, when a slaves dies, he is no longer in slavery, death frees him from slavery. Since Christ “has died for all, then all have died” (II Cor. 5:14). His death is our death. Since we have died with Him and He has died to sin, then we have died to sin. We are freed from the slavery of sin and are no longer enslaved to it (Rom. 6:6-7). But now Christ is alive, having been raised from the dead, and we are made alive to God in Him. His resurrection is our resurrection. “But the life He lives He lives to God” (Rom. 6:10b). This is the life of righteousness, the righteousness of faith. And so we, who are now alive to God in Him, are to live to righteousness. For just as death produces sin, so life produces righteousness.

“And He Himself bore our sins in His body on the cross, that we might die to sin and live to righteousness; for by His wounds you were healed.” (I Pet. 2:24).

Christ bore our sins to take them away (to redeem us from sin) so that we might die to sin with Christ and be made alive to righteousness in His resurrection. Having been redeemed from the slavery of sin through the death of Christ, we who are now alive in Him have become slaves of righteousness (Rom. 6:17-18), that is, slaves of Christ who is our righteousness (I Cor. 1:30). Redemption is salvation from sin to righteousness.

Since in those days of the Old and New Testament, slaves were also sold at the market, to buy a slave at the slave market could also be called “redemption.” The context of the verbs translate “to redeem” is not the law court but the slave market and has nothing to do with “paying the penalty.” The purchase price or ransom is not the penalty for breaking the law but is the means by which the purchase is accomplished. A ransom is given instead or in place of those who are to be redeemed or delivered; it has nothing to do with a substitute paying the penalty of sin to satisfy the justice of God. The context of the words translated “to redeem” or “redemption” is not the law nor the courtroom but slavery and the slavemarket. The redemption of Israel from bondage in Egypt has nothing to do with a substitute paying the penalty of sin; and neither does the redemption in Christ Jesus by His death [His blood] have to do with a substitute paying the penalty of sin, but with delivering us from bondage and freeing us from the slavery of sin. In the II Cor. 5:21 and Gal. 3:13 passages, “made to be sin” or “a curse” does not mean paying the penalty of sin. In his second letter to the Corinthians Paul writes,

“He who knew no sin was made to be sin for us, in order that we might become the righteousness of God in Him.” (II Cor. 5:21 ERS).

Historically, there has been three interpretations of the phrase “made to be sin” in this II Cor. 5:21 passage:

1. When Christ in His incarnation took on human nature, which is “in the likeness of sinful flesh” (Rom. 8:3), God made Him to be sin.

2. Christ in becoming a sacrifice for sin was made to be sin, the word “sin” (harmartia) meaning a “sacrifice for sin” (Augustine and the NIV margin “be a sin offering”).

3. Christ is treated as if He were a sinner, and as such Christ became the object of God’s wrath and bore the penalty and the guilt of sin (the traditional Protestant interpretation).

In the first interpretation, it is assumed that Christ’s death is a participation, on the behalf of and for the sakes of sinful humanity.

And in the second interpretation, the basic concept is sacrifice, but the sacrifice has been usually assumed to be a substitution, not as a participation.

In the last interpretation, it is assumed that Christ’s death is a vicarious act, a substitution, in the stead of sinful humanity.

But this substitution interpretation must here be rejected because it is contrary to the explicit statement in the verse which says that he was made sin “for us”, that is, “on our behalf” (huper hemos, NAS; see verses 14-15, and 20). Christ was made to be a sin-sacrifice for us to save us from sin, to take away our sin (John 1:29). And Christ was made a sin sacrifice to take away our sin

“in order that we might become the righteousness of God in Him.”

That is, that we might be set right with God in the risen Christ. As we have already seen, the righteousness of God is the activity of God to set us right with God; that is, to save us from sin (trust in false god) to righteousness (trust in the true God). Christ participated in our spiritual death to save us from sin (trust in a false god), so that we could participate in the risen Christ, being saved from death to life and hence being saved from sin to righteousness (trust in the true God).

The substitution interpretation of Christ’s sacrifice does not understand this participation and just assumes a legalistic substitution interpretation of Christ’s death as a paying the penalty of sin for us. This misintrepretation of this Scripture is based on a legalistic misunderstanding of the righteousness of God as the justice of God. But as we saw above, this justice is not the Biblical concept of the righteousness of God. This legalistic misunderstanding reduces and equates the righteousness of God to justice, that is, the giving to each of that which is due to them with a strict and impartial regard to merit (as in Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics). It is this concept of righteousness that gave Luther so much trouble.

Martin Luther rediscovered the meaning of the righteousness of God in Paul’s letter to the Romans. But Luther, using the scholastic distinction between the active and passive righteousness, rejected the equation of the righteousness of God to the active righteousness, whereby God proves Himself to be righteous by punishing the sinners and the unjust. But Luther equated the righteousness of God to the passive righteousness, whereby God gives righteousness to the one that is passive, does no works to receive it, but receives it by faith. That is, Luther gave the impression that the righteousness of God is the righteousness from God.

Now Luther’s discovery of the righteousnes of God was lost by those who came after him, the Protestant scholastics. Luther’s use of the scholastic distinction of active and passive righteousness tended to obscure the Biblical concept of the righteousness of God. Luther obviously rejected the active sense; but the later Lutheran Protestant Scholastics interpreted Luther as accepting both senses. They also accepted the active righteousness interpreting the righteousness of God as the justice of God that was satisfied by the passive obedience of Christ on the cross paying the penalty for man’s sin that the justice of God required before man’s sins can be forgiven. Because their explanation of the death of Christ was still grounded in the legalistic concept of justice, that is, that Christ died to pay the penalty for man’s sin which the justice of God requires to be paid before God can save man, they had to retain the active sense also. Thus Luther’s discovery of the Biblical understanding of the righteousness of God was obscured and eventually lost.

The later Prostestant Scholastics interpreted the righteousness from God as the merits or righteousness of Christ earned by Christ’s active obedience. Luther’s apparent identification of the righteousness of God with the righteousness from God lead eventually to the equating of the righteousness from God with Christ’s righteousness, that is, the merits of Christ, which Christ earned by His active obedience before He died on the cross and is imputed to the believer’s account when he believes. Scripture was often misinterpreted in terms of this identification. For example, Paul’s statement that “in him we might become the righteousness of God” (II Cor. 5:21b) is interpreted to mean that the righteousness of God is the righteousness from God. Therefore, the believer is righteous by the “righteousness of God in Christ” which is interpreted as the merits of Christ that was earned by Christ’s active obedience before He died on the cross and is imputed to the believer’s account when he believes. Thus righteousness from God is misunderstood as merits and the righteousness of God as the justice of God that bestows those merits. Thus the righteousness from God is the righteousness of God.

But the righteousness from God is not the righteousness of God. These are different though related ideas and must be carefully distinguished. Now since the righteousness of God, as we saw above, is God setting right the wrong, then the righteousness of God here is the deliverance or saving of us from our sins in Him, in Christ’s death and resurrection. But the righteousness from God is the righteousness of faith. Paul writes in his letter to the Philippians,

“3:8b For his sake I have suffered the loss of all things, in order that I may gain Christ 3:9and be found in him, not having a righteousness of my own, based on law, but that which is through faith, the righteousness from [ek] God that depends upon [epi] faith, …” (Phil. 3:8b-9).

Thus the righteousness from God is the righteousness of faith (Rom. 4:13) which is that right personal relationship to God that results from faith in the true God (Rom. 4:3). Paul writes in his letter to the Romans:

“4:3 For what does the scripture say? ‘Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness.’ 4:4Now to one who works, his wages are not reckoned as a gift but as his due. 4:5And to the one who does not work but trusts him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is reckoned as righteousness …. 4:13The promise to Abraham and his descendants, that they should inherit the world, did not come through the law but through the righteousness of faith.” (Rom. 4:3-5, 13)

Faith in God is reckoned as righteousness (Rom. 4:5). That is, to trust in God is to be righteous. This is the righteousness of faith (Rom. 4:13) and the righteousness from God (Phil. 3:9). That is, the righteousness of faith is not merit placed to the account of the believer, but it is the right relationship of the believer to God by faith. The righteousness of faith is the act or choice of a man to trust God and the righteousness of God is the act or activity of God to set a man right with God Himself by faith. The righteousness of God is what God does and the righteousness of faith is what man does in response to God’s activity. Thus the righteousness of faith is not the righteousness of God.

But the righteousness of faith is the righteousness from God. Since this act of faith by a man is possible only when God acts to set a man right with God Himself by the righteousness of God, then the righteousness of faith is the righteousness from God.

But as we just saw, this righteousness of faith is not the righteousness of God. Thus the righteousness from God is not the righteousness of God. Luther’s apparent identification of the righteousness from God with the righteousness of God was wrong and unscriptural.

Now this idea that the righteousness of God is the justice of God, that is, that attribute of God which requires that God punish all sin and reward all meritorious works, also leads to the misinterpretation of the first part of II Cor. 5:21 (“For our sakes he made him to be sin who knew no sin,”), that the sinless Christ was identified with the sin of the sinner, including the guilt of that sin and its consequence of death, of separation from God; Christ paid the consequences of that sin by His death on the cross. This intrepretation is based on the penal substitution theory of the atonement.

But as we saw above, this substitution interpretation must here be rejected because it is contrary to the explicit statement in the verse which says that he was made sin “for us”, that is, “on our behalf” (huper hemos, NAS; see verses II Cor. 5:14-15, and 20), not “instead of” as a substitute.

But since the phrase “made sin” may mean “scarifice for sin” (or “sin-offering”), Paul may be only intending to say no more than that Christ was made a sin-offering. But Christ was made to be a sin-sacrifice for us to save us from sin, to take away our sin (John 1:29). Thus Christ was made a sin sacrifice to take away our sin “in order that we might become the righteousness of God in Him” (II Cor. 5:21b ERS). That is, that we might be set right with God in the risen Christ. And as we have already seen, the righteousness of God is the activity of God to set us right with God; that is, to save us from sin (trust in false god) to righteousness (trust in the true God). As Christ was made a sin-scarifice for us, He participated in our spiritual death to save us from sin (trust in a false god), so that we could participate in the risen Christ, being saved from death to life and hence being saved from sin to righteousness (trust in the true God).

Thus “we might become the righteousness of God in Him” (II Cor. 5:21b ERS). That is, that we might be saved (“the righteousness of God”) in the risen Christ. And when Apostle Paul writes to the Galations,

“Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law, having become a curse for us — for it is written, ‘Cursed be everyone who hangs on a tree'” (Gal. 3:13),

Paul does not mean that Christ paid the penalty of sin as our substitute, but that Christ’s death was to deliever us (“redeemed”) from our sins and to save us from the wrath of God (“the curse of the Law”, see Gal. 3:10). And Christ being made a curse for us, does not mean that Christ died as a substitute, in our place, paying the penalty of our sins, but that Christ’s death was “for us”, on our behalf (huper hemos), The Scripture that Paul here quotes (Deut. 21:23) does not mean that being made a curse was for another’s sins but because he was being hung on a tree for his own sins (Deut. 21:22). And since Christ was hanging on the tree (the cross) was not because of His own sins (He was without sin – II Cor. 5:21) but it was on our behalf to redeem us from our sins and from God’s wrath against our sins (Rom. 1:18). Paul does not say that Christ took our curse but that He became a curse for us to redeem us from the curse of the law. Christ’s death sets us free from the law and from its curse.

The introduction of these legalistic concepts into the interpretation of these passages has obscured their meaning and interpretation. Apart from the clear and explicit statement of Scripture, it cannot be assumed that this is what these verses mean. Since this legalism is contrary to the clear and explicit statements of Scripture, any interpretation employing these legalistic concepts is suspect. In fact the Scripture explicitly rejects the principle of vicarious penal sacrifice upon which this interpretation depends.

“The person who sins will die. The son will not bear the punishment for the father’s iniquity, nor will the father bear the punishment for the son’s iniquity; the righteousness of the righteous will be upon himself, and the wickedness of the wicked will be upon himself.” (Ezekiel 18:20 NAS; see also Deut. 24:16; Jer. 31:30).

If Christ did not die to pay the penalty for man’s sin and satisfy God’s justice, then why did Christ have to die to save man? Why then do men need to be saved? An examination of Scripture (John 10:10; Eph. 2:4-5; Heb. 2:14-15; I John 4:9; etc.) clearly shows that the answer to this question is that man needs to be saved because he is dead. Man is separated and alienated from God (Eph. 4:8). He does not know God personally, and because he does not know the true God, he turns to false gods – to those things which are not God – and makes those into his gods (Gal. 4:8). The basic sin is idolatry (Ex. 20:2; Rom. 1:25), and man sins (chooses these false gods) because he is spiritually dead – separated from the true God. And all men have sinned because they are spiritually dead. This is what the Apostle Paul says in the last clause of Romans 5:12 ERS: “because of which [death] all sinned.” [1]

“Therefore, as through one man sin entered into the world, and death through sin, and so death passed unto all men, because of which all sinned: – ” (Rom. 5:12 ERS).

Spiritual death which “spread to all men” along with physical death is not the result of each man’s own personal sins. On the contrary, a man sins as a result of spiritual death. He received death from Adam, from his first parents. The historical origin of sin is the fall of Adam – the sin of the first man. [2] Adam’s sin brought death – spiritual and physical – on all his descendants (Rom. 5:12, 15, 17). [3] This spiritual death inherited from Adam is the personal, contemporary origin of each man’s sin. Because he is spiritually dead, not knowing God personally, he chooses something other than the true God as his god; he thus sins.

This is why a man needs to be saved. He is dead spiritually and dying physically. Man needs life – he needs to be made alive – to be raised from the dead. And if he receives life, if he is made alive to God, death which leads to sin is removed. And if death which leads to sin is removed, then man will be saved from sin. Thus salvation must be understood to be primarily from death to life and secondarily from sin to righteousness. And since God’s wrath – God’s “no” or opposition to sin – is caused by sin (Rom. 1:18), the removal of sin brings with it also the removal of wrath. No sin, no wrath. Salvation is then thirdly from wrath to peace with God (Rom. 5:1, 9).

This salvation (from death, sin and wrath) is exactly what God accomplished through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, His Son. This is why Christ died, that He might be raised from the dead. Jesus entered into our spiritual death in order that as He was raised from the dead, we might be made alive in and with Him (Eph. 2:5). And by saving us from spiritual death, Christ saves us from sin. It is by taking away the spiritual death which leads to our sin that God takes away our sin. Jesus died for our sins – literally – to take them away (John 1:29). What the Old Testament sacrifices could not do (Heb. 10:1-4) the death of Christ has done. The blood of Jesus (His death) cleanses us from our sins (I John 1:7). We are delivered from sin itself. We were saved from our trust in false gods when we put our trust in Jesus Christ and the true God who sent Him. We “turned from idols to serve the living and true God” (I Thess. 1:9). When we were spiritually dead we trusted in and served those things that are not God – money, power, sex, education, popularity, pleasure, etc. But when we turned to the risen Christ, we entered into life, leaving behind those false gods. The risen Jesus Christ is now our Lord and our God (John 20:28).

The death and resurrection of Jesus was the means by which God removed death – the barrier to knowing God personally and knowing His love. In the preaching of the Gospel God reveals Himself to us making us spiritually alive to Himself when we receive Jesus Christ who is the life (John 14:6; I John 5:12). To be spiritually alive is to know God personally, and to know God personally is to trust Him. For God is love (I John 4:8, 16) and love begets trust. The trust that God’s love invokes in us is righteousness (Rom. 4:5, 9); it relates us rightly to God. Thus by making us alive to Himself, God sets us right with Himself through faith. Life produces righteousness just as death produces sin.

The righteousness of God is God acting in love for the salvation or deliverance of man. This righteousness of God has been manifested, that is, publicly displayed, in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ (Rom. 3:21-22). God was active in Jesus Christ, particularly in His death and resurrection, for salvation (Acts 4:12; I Thess. 5:9; I Tim. 2:10; 3:15; Heb. 5:9). Because He is the act of God for our salvation, Jesus Christ is the righteousness of God (I Cor. 1:30). The gospel or the good news is about this manifestation of the righteousness of God. The gospel tells us about God’s act of salvation in the person and work of Jesus Christ (Rom. 1:1-4; I Cor. 15:3-4; Eph. 1:13). God acted in Him to deliver man from death, from sin, and from wrath. But since wrath is caused by sin and sin is caused by death, salvation is basically the deliverance from death to life. Man cannot make himself alive. Only God can make alive for He is the living God and the source of all life. And God did this through the death and the resurrection of Jesus. Because God loves man, He did not leave him in death but has provided for him deliverance from death by sending His Son into the world.

“For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth on him should not perish, but have eternal life.” (John 3:16 KJV).

Thus God in His love for man sent His Son to become a man, Jesus Christ, the God-man (John 1:14). He was the perfect man; He lived in perfect fellowship with God, His Father, and perfectly trusted God throughout His entire life (John 1:4; 8:28-29; 12:50; 16:32; 17:25). But He came not just to be what we should have been or to give us a perfect example; He came to die on our behalf in order that we might have life in Him. Jesus said,

“10:10 I came that they might have life, and have it more abundantly. 10:11 I am the good shepherd: the good shepherd giveth his life for the sheep.” (John 10:10-11 KJV).

And the Apostle John said,

“In this was manifested the love of God toward us, because that God sent his only begotten Son into the world that we might live through him.” (I John 4:9).

He entered not only into our existence as man, but He entered into our condition of spiritual and physical death. On the cross He died not only physically but spiritually. For only this once during His whole life was He separated from His Father. “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” (Matt. 27:46 KJV) He was forsaken for us; He died for us.

“By this we know love, because he laid down his life for us” (I John 3:16 ERS).

But God raised Him from the dead. He entered into our death in order that as He was raised from the dead we might be made alive with and in Him (Eph. 2:5). Hence Christ’s death was our death, and His resurrection is our resurrection (II Cor. 5:15). He became identified with us in His death in order that we might become identified with Him in His resurrection and have life. He became like us that we might become like Him. As the second century Christian theologian and bishop of Lyon, Irenaeus (125-202 A.D.), said,

“… but following the only true and steadfast teacher, the Word of God, our Lord Jesus Christ, who did, through His transcendent love, become what we are, that He might bring us to be even what He is Himself.” [1]

The writer to the Hebrews also wrote,

“But we see Jesus, who was made a little lower than the angels, … so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone.” (Heb. 2:9 NIV).

“2:14 Since therefore the children share in flesh and blood, he himself likewise partook of the same nature, that through death he might destroy him that has the power of death, that is the devil, 2:15 and deliver all those who through fear of death were subject to lifelong bondage.” (Heb. 2:14-15)

He acted as our representative, on our behalf and for our sakes. The Greek preposition huper does not mean “instead of” but “on the behalf of” or “for the sake of”. In the following passages, for example, the Greek preposition huper cannot mean “instead of”.

“For it has been granted to you that for the sake of [huper] Christ you should not only believe in him but also suffer for his sake [huper autou, on the behalf of him]” (Phil. 1:29).

“It is right for me to think this about all of you [huper pantan humon], because I have you in my heart, since both in my bonds and in the defense and confirmation of the Gospel you all are partakers of grace with me.” (Phil. 1:7 ERS).

“12:5 On the behalf of [huper tou toitotou] such a man I will boast, but on behalf of myself [huper emautou] I will not boast, except of my weaknesses. 12:6 For if I wish to boast, I shall not be foolish, for I shall be speaking the truth; but I refrain from this lest anyone reckon to me above what [huper ho] he sees in me or hears from me, 12:7and by the surpassing greatness [huperbole] of the revelations. Wherefore, in order that I should not be exalted [huperairomai] there was given me a thorn in the flesh, a messenger of Satan to harass me, in order that I should not be exalted [huperairomai]. 12:8About this [huper touton]

I besought the Lord that it should leave me; 12:9 and He said to me, ‘My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is perfected in weakness.’ Most gladly therefore I will boast in my weaknesses, that the power of Christ may rest on me.” (II Cor. 12:5-9 ERS).

Thus the Greek preposition huper does not mean “instead of” but “on the behalf of” or “for the sake of”. And thus Chirst died on the behalf of all men, not instead of them;

“For the love of Christ constraineth us; because we thus judge, that one died for all [huper panton, on the behalf of all],

therefore all have died,” (II Cor. 5:14).

that is, in Christ who represents all.

“And he died for all [huper panton, on the behalf of all], that those who live might live no longer for themselves but for him who for their sake [huper auton, on the behalf of them] died and was raised.” (II Cor. 5:15).

Adam acting as a representative brought the old creation under the reign of death. But Christ acting as our representative, on our behalf, brought a new creation in which those “who have received the abundance of grace and the gift of righteousness will reign in life” (Rom. 5:17).

“15:21 For since by man came death, by man came also the resurrection of the dead. 15:22 For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive.” (I Cor. 15:21-22).

“Wherefore if any man is in Christ, he is a new creature: the old things are passed away; behold, they are become new.” (II Cor. 5:17).

[Jesus said]

“Because I live ye shall live also.” (John 14:19 KJV).

Acting through our representative, God has reconciled us to Himself through Christ, that is, God has brought us into fellowship with Himself.

“5:18 But all things are of God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ … 5:19 to wit, that God was in Christ reconciling the world unto himself ….” (II Cor. 5:18-19; see also Rom. 5:10-11; I Cor. 1:9; I John 1:2-3).

This representative work of Christ should be understood, not as a vicarious act, instead of another, but as a participation, an act of sharing in the condition of another. Christ took part or shared in our situation. He entered, not only into our existence as a man, but also into our condition of spiritual and physical death.

“2:14 Since therefore the children share in flesh and blood, he himself likewise partook of the same nature, that through death he might destroy him that has the power of death, that is the devil, 2:15 and deliver all those who through fear of death were subject to lifelong bondage.” (Heb. 2:14-15).

On the cross, Jesus died not only physically but also spiritually (“My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” Matt. 27:46), sharing in our spiritual death. We are reconciled to God through the death of Christ (Rom. 5:10) because He shared in our death (Heb. 2:9). But He was raised from the dead, and that on behalf of all men (II Cor. 5:15). He was raised from the dead so that we might participate and share in His resurrection and be made alive with Him.

“2:4 But God, being rich in mercy, because of His great love with which He loved us, 2:5 even when we were dead in offenses,

made us alive together with Christ (by grace you have been saved), 2:6 and raised us up with Him, and seated us with Him in heavenly places, in Christ Jesus;” (Eph. 2:4-6 ERS).

His resurrection is our resurrection. He was raised from dead for us so that we might participate in His resurrection and have life, both spiritual and physical. Thus the representative work of Christ is a participation, an act of sharing in the condition of another. He participated in our death so that we could participate in His life.

Since spiritual death is no fellowship with God (it is the opposite of spiritual life which is fellowship with God), then being made alive with Christ we are brought into fellowship with God. Hence we are reconciled to God (Rom. 5:10; II Cor. 5:17-19). The Greek word katallage, which is translated ” reconciliation” in our English versions, means a “thorough or complete change.” Hence it refers to a complete change in the personal relationship between man and God. Because man is dead, he has no personal relationship with God, no fellowship with God. When a man is made alive to God with Christ, he is brought into a personal relationship with God, into fellowship with God. His personal relationship to God is completely changed, changed from death to life. Reconciliation can, therefore, be defined as that aspect of salvation whereby man is delivered from death to life. And the source of this act of reconciliation is the love of God. It is a legalistic misunderstanding of reconciliation to say that God was reconciled to man. The Scriptures never say that God is reconciled to man but that man is reconciled to God (Rom. 5:10; II Cor. 5:18-19). The problem is not in God but in man. Man is dead and needs to be made alive. Man is the enemy of God; God is not the enemy of man. God loves man, and out of His great love He has acted to reconcile man to Himself through the death and resurrection of Christ. It is true that God in His wrath opposes man’s sin and in His grace has provided a means by which His wrath may be turned away. But this aspect of salvation is propitiation, not reconciliation. Reconciliation should not be confused with propitiation. God in reconciling man to Himself has saved man from death, the cause of sin, and hence He has removed sin, the cause of His wrath – no sin, no wrath. Christ’s death is a propitiation because it is a redemption and it is a redemption because it is a reconciliation, salvation from death to life.

To Continue, Click here.